Yom Kippur War 1973

War

The Egyptian Front

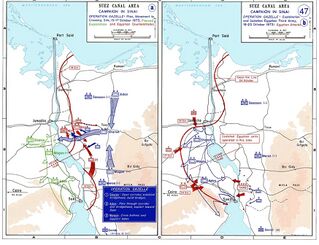

On October 6, 1973, at 2:00 p.m.--the afternoon of Yom Kippur, the holiest day on the Jewish calendar--Egypt launched a surprise attack across the Suez Canal, marking the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War. The assault, which began four hours earlier than Israeli intelligence had anticipated, caught the IDF in the midst of its partial mobilization.[1] Simultaneously, Syria launched a surprise assault on the Golan Heights.

Within the first two hours, over 23,000 Egyptian soldiers and tanks poured across the canal on quickly constructed pontoon bridges, overwhelming the fewer than 450 poorly trained Israeli reservists stationed along the Bar-Lev Line, a chain of Israeli fortifications built to defend the eastern bank.[2] The Rebbe had previously warned Israeli leaders about the line’s vulnerabilities,[3] which were soon exploited by Egyptian forces. Most of the Bar-Lev Line's fortifications were quickly overrun, with only Fort Budapest, the northernmost outpost, managing to resist the onslaught.[4] Before long, over half of the soldiers stationed along the line perished or were taken prisoner.[5]

By the following day, Egypt had deployed five infantry divisions—approximately 100,000 soldiers—along with 1,300 tanks and 2,000 artillery pieces, across the canal, onto its eastern bank. These forces established five bridgeheads, each measuring roughly one mile deep and four miles wide.[6]

The Syrian Front

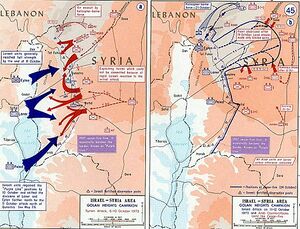

On the northern front, Israeli defenses consisted of 177 tanks and 11 artillery batteries, manned by 200 infantrymen across ten strongpoints along the 40-mile front. Facing them, Syria deployed 1,400 tanks, 115 artillery batteries, and three infantry divisions totaling 40,000 men. Despite superior Israeli operational effectiveness, after Syria unleashed its forces on the unprepared IDF presence, considerable portions of the southern Golan Heights were lost, and Israeli casualties were significant.[7]

The most critical threat to Israel emerged in the southern Golan Heights, where, on October 7, Syrian forces had a clear path to advance toward major Israeli population centers near the Sea of Galilee.

By the afternoon of the following day, approximately 600 Israeli soldiers were killed on both fronts, with hundreds more wounded, and over 200 captured. The IDF also lost about 300 tanks and 34 aircraft. These were the most significant casualties Israel had ever endured in such a brief period, leaving the IDF leadership in a state of shock and alarm.[8]

Amid this crisis, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan warned Prime Minister Golda Meir that “a holocaust was about to engulf the country,” proposing a major retreat on both fronts. As the situation deteriorated, Israel’s leadership resolved to prepare the country’s nuclear arsenal for possible deployment in the event of a total battlefield collapse.[9]

The scale and suddenness of the attack—occurring on Yom Kippur, the holiest day on the Jewish calendar—shocked the Israeli public, who had believed that the post-1967 regional status quo would ensure a decade of peace. The abrupt mobilization, which saw men called directly from synagogues to the front lines, coupled with the casualties and chaotic reports from the battlefield, plunged Israeli society into a state of mourning and collective trauma. A deep uncertainty prevailed over whether the state would survive.[10]

On October 7, the day after Yom Kippur, the Rebbe sent a message through Gershon Ber Jacobson, editor of the Algemeiner Journal and special correspondent for the Israeli newspaper Yediot Ahronot, to be shared in Israel:

- Write to them not to worry. In the end, there will be many miracles and great victories—greater even than those of the Six-Day War. But they must not tarry. The military must be allowed to operate according to its understanding. The politicians are interfering and causing delays when there is no time to wait.

- The Jews must ensure that they are not fooled into trading a full-scale victory for something of no value. The Israeli government must not succumb to pressure from the superpowers and the U.N., and must instead direct the IDF to capture as much territory as possible in Syria and Egypt, as quickly as possible.[11] Every delay will mean the forfeiture of a major opportunity and will come at the cost of many casualties.”[12]

Israeli forces mounted a determined defense, managing to slow the Syrian advance. Through intense battles, the IDF stabilized the front lines by October 8, halting the offensive and preventing deeper Syrian penetration.[13]

In the Sinai, following Egypt’s initial advance, Israeli forces had only a minimal presence standing between the Egyptian army and the Israeli interior. Caught off guard and lacking armor in the forward area, the IDF was unable to mount an immediate response. This created a window of opportunity for Egyptian forces to advance into the Sinai at a time when the Israeli Air Force was not in a position to provide effective defensive airpower.[14] However, expecting an imminent Israeli response, the Egyptians halted and entrenched.[15]

The Rebbe later described the fact that the Egyptians did not advance to Jerusalem and Tel Aviv as a miracle:[16]

- The greatest miracle was that the Egyptians stopped their invasion for no good reason, only a few miles east of the Canal! The obvious[17] military strategy would have been to encircle a few fortified positions in the rear, and with the huge army of 100,000 men armed to the teeth, to march forward in Sinai, where at that point in time there was no organized defense of any military consequence. This is something that cannot be explained in the natural order of things.[18]

The Rebbe compared Egypt’s unlikely restraint to the failure of the Maginot Line in World War II:

- Anyone who was in France during World War II—or has read about that time—knows that the French built a heavily fortified defensive line, far stronger than the one in Sinai. But when the Germans concentrated their armored forces and broke through a single point . . . the French completely lost their footing. The Germans were then able to break through, reach the sea, and [effectively] conquer all of France in a single day. It took only a few more days to complete the occupation in full detail . . .

- This is well known, especially among those who study military tactics, where World War II is taught first and foremost—having occurred only recently. In the natural order, the Egyptians too could have done the same, Heaven forbid.

- Moreso: In order to conquer France during WWII, the Germans needed to pass through numerous cities, each with military forces stationed there. In contrast, here there was only desert—no settlements, and hardly any soldiers or tanks. There was nothing that could have stopped the Egyptians. . .[16]

Spiritual Efforts

On October 9 (13 Tishrei), at a gathering marking the anniversary of the passing of the fourth Chabad Rebbe, the Rebbe urged Jews globally to counter the adversity with a spiritual response. Emphasizing the spiritual power of joy, he explained that “joy has the power to breaks all boundaries” and serves as a conduit to elicit blessings for the Jewish people everywhere:

- At first glance, this might seem hard to understand: When Jews are under attack, how could we hold a festive gathering? . . .

- The Baal Shem Tov would often teach the verse, “G-d is your shadow” (Psalms 121:5), explaining that just as a person’s shadow moves exactly as they do, so too, G-d mirrors a Jew’s actions—the way a person behaves below is reflected above.

- This idea is also expressed in the Zohar, which states . . . that a Jew’s demeanor in this world determines how they are treated from above. When a person radiates joy, joy is reflected back to them from Heaven.

- In light of all this, it’s clear that the best way to help during times like these is through joy—because joy has the power to break through all barriers, even the barrier of physical distance.[19]

Counteroffensive

By October 10, Israeli forces had largely repelled Syrian troops to the post-1967 borders and initiated a counteroffensive into Syrian territory.[20] On October 11, the IDF established a salient approximately 12 miles wide and 20 miles deep, reaching within 30 miles of Damascus.[21] This position provided a strategic buffer and posed a direct threat to the Syrian capital.[22]

In the Sinai Peninsula, Egyptian forces initially held the advantage. However, on October 14, the ninth day of the war, the Egyptian army launched a large-scale assault aimed at capturing the strategic Gidi and Mitla Passes. This maneuver required an eastward advance that forced Egyptian armored units to move beyond the protective range of their surface-to-air missile (SAM) defenses.

Anticipating the attack, the IDF had strategically positioned their forces on elevated terrain, which now subsequently engaged the advancing Egyptian forces. As well, once Egyptian armored units moved beyond the coverage of their SAM defenses, they became vulnerable to aerial attacks, allowing the Israeli Air Force to strike and inflict heavy losses. By the end of the day, Israeli intelligence estimated that the Egyptian forces had lost approximately 280 tanks.[23] In contrast, the Israeli losses that day were minimal, with fewer than 40 tanks damaged, and all but six were repaired and returned to active duty.[24]

On October 15, the IDF's Southern Command, under the leadership of Major General Ariel Sharon, initiated operations to cross the Suez Canal and enter Egyptian territory.[25] Upon crossing, they encountered unexpectedly fierce resistance at an Egyptian agricultural research facility, which Israeli soldiers referred to as the “Chinese Farm.” Israeli forces targeted key Egyptian SAM sites and radar stations, significantly weakening Egypt's air defense network.[26]

By October 18, the IDF had successfully reinforced its positions on the western bank of the Suez Canal and began advancing further into Egyptian territory.[27]

By October 23, Israeli forces had surrounded the Egyptian Third Army, near Suez City on the western bank.[28] With this strategic encirclement, the Third Army’s supply lines were cut.

Israeli forces had the capability to advance the remaining 60 miles to Cairo, a move that could have potentially toppled President Sadat’s regime.[29]

March on Enemy Capitals

Despite having a clear path to Damascus, Dayan instructed the IDF to halt their advance within 30 miles from the Syrian capital.[18][30]

The Rebbe strongly opposed this decision.[31] In public addresses and private communications with Israeli officials throughout October, he outlined a comprehensive argument in favor of temporarily capturing the Syrian capital. He maintained that such a move would secure decisive military, diplomatic, and long-term strategic advantages, each of which would have saved lives:

- Tactical advantage: The Rebbe contended that seizing Damascus in the early days of the war would deprive Syria of the capability to pose further resistance and compel it to seek an immediate peace settlement. This, in turn, would have curtailed further Iraqi involvement and prevented Saudi Arabia and Jordan from joining the conflict. Additionally, this would have neutralized an entire front and freed up 40,000 Israeli soldiers and significant military equipment for redeployment elsewhere.[32]

- Long-term deterrence: The Rebbe asserted that Damascus symbolized the fortitude of the Arab world. He warned that without subduing Syria, no true peace would be achieved with the Arab world.[33] Furthermore, he believed such an action would restore the sense of deterrence instilled by the success of the Six-Day War and would reinforce Israel’s strength in the eyes of the Arab world.[25][34] …….

- Israeli prisoners of war: Capturing the capital would have provided Israel the opportunity to free their men captured by the Syrians, sparing many lives and avoiding the prolonged war of attrition with Syria. [35]

The Rebbe argued that halachic principles of defense, applied to the situation at hand, mandated the march on Damascus.[36] According to Torah, the culmination of a military operation requires the complete submission of the enemy. The Torah's fundamental rule of self-defense dictates that threats must be comprehensively deterred and, when necessary, neutralized.[37]

On the fifth day of the war, Rabbi Binyamin Klein, the Rebbe's secretary, called Yossi Ciechanover, General Counsel to the Israel Ministry of Defense, on the Rebbe's behalf. He requested that Ciechanover relay a message to Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, urging Israel to capture Damascus. Ciechanover recalled:

- Dayan took it very seriously. He said to me, “Go back to the Rebbe and tell him that I really appreciate his approach and I understand where he’s coming from—but I still have a problem. There is still war on all fronts: in Jordan, in Jerusalem, and in the Sinai. If I go into Damascus, the next day I’ll have to feed three million Arabs there.

- “Second, I have to take the entire army and move them up to the north to ensure safety and order in the area. I cannot do it from a manpower point of view.

- “So tell him that I really appreciate it and explain to him the reasons why I cannot do it.”

- I called back [. . .] The Rebbe's answer was, “It's a big mistake. It's a big mistake.”[38]

Counter Arguments

In response to claims by Israeli officials about the IDF’s decision to halt their advance on Damascus, the Rebbe recounted a conversation with an Israeli official in which he challenged him as to why the IDF halted their advance toward Damascus midway through their campaign:

- When I asked why Damascus wasn’t taken, the answer I got was: “Because the area is full of cliffs and rocky terrain—it’s too difficult.” Had I not heard it myself, I wouldn’t have believed it. They were able to conquer everything else—but suddenly, rocks were the obstacle?[39] The absurdity of the excuse only proves how strong the question really is.[40]

On Simchat Torah (October 19, 1973), Israeli Consul to New York Shlomo Levin and Aryeh Morgenstern, Director of the World Zionist Organization's Torah Department in the United States, led a delegation to 770 for hakafot. During an extended conversation with the Rebbe about the ongoing war, the Rebbe expressed optimism that Israel could avoid becoming mired in the conflict and praised the IDF's performance.

He then urged them to convey a message to the government that Israel should seize Damascus, emphasizing that Israel was obligated to act in its own security interests.

In response to the claim that it would cost the IDF many casualties, the Rebbe argued that the hesitation to advance and the defensive posture held by the army had already resulted in greater casualties than a decisive offensive would have caused.

Addressing Israeli doubts about whether the United States would support such an operation, the Rebbe pointed out that America had a vested interest in Israel’s victory over Syria and would therefore back these actions.[41] Citing “reliable contacts in Washington,” he stated that the United States would have ultimately “understood and forgiven” an Israeli conquest of Damascus.[34]

The Rebbe firmly rejected concerns that seizing Damascus would provoke Soviet intervention. He insisted that the Soviet threat amounted to mere posturing and did not constitute a genuine cause for concern.[42]

At the conclusion of the conversation, the Rebbe urged Levin and Morgenstern to contact any officials they could reach in Israel that night—whether government ministers, military commanders, or party leaders—and convey his position that Damascus must be taken. Levin contacted Prime Minister Golda Meir’s office, while Morgenstern reached out to Knesset members Zevulun Hammer and Yitzchak Raphael of the National Religious Party. Both Knesset members reported that Defense Minister Moshe Dayan was unwilling to advance beyond the pre-war borders due to fears of Soviet retaliation.[34]

In a public address on October 27, the Rebbe elaborated:

- As for the argument that Israel had to take Washington’s position into account—the reality is that the U.S. was hoping Damascus would fall and another front would be eliminated. In fact, they wanted this even more than Israel did, because Israel had already agreed to [return to] the 1967 borders[43]—whereas Washington favored maintaining the current lines. However, for diplomatic reasons, the U.S. outwardly opposed the move, preferring to maintain plausible deniability and avoid Arab backlash. But in truth, they hoped Israel would disregard their statements and present them with a fait accompli.[44]

U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger encouraged the Israelis to capture Damascus to give Israel a dominant negotiating position and enable it to dictate a peace settlement on its own terms that would secure its long-term security.[45] In a remark to Israeli Ambassador Simcha Dinitz, he quipped, “When you reach the suburbs, you can use public transportation.”[46]

The Rebbe later noted an additional reason that the move would have received backing from the United States: Even a brief capture of Damascus would have enabled Israel to seize Soviet war plans stored there—an intelligence asset of significant value to the U.S.[47]

Shortly after the war, Knesset member Avraham Verdiger had a brief audience with the Rebbe, together with his wife, Chaya. During the meeting, she asked how a small, isolated country like Israel could have allowed itself to capture and hold Damascus. The Rebbe clarified:

- “What I meant was that Israel should have entered Damascus, rescued the Israeli POWs, the wounded, and anyone else whose lives could have been saved—and then withdrawn immediately. I never meant for Israel to settle there.”[48]

According to Morgenstern, the Rebbe didn't consider it critical to continue pursuing the Egyptians at that point. However, in Brigadier General Ran Ronen-Pecker’s account of his private conversation with the Rebbe, he shared:

- [The Rebbe] said to me, “Listen, the Yom Kippur War had bad results…”

- “Look, Rabbi,” I said. “From a military perspective, we succeeded. We arrived 101 kilometers from the Egyptian capital, and within 40 kilometers of the Syrian capital.”

- “No,” he objected. “To win a war means to conquer the capitals.”

- “What is this that General Sharon is saying, that he had no fuel?” the Rebbe asked. “He could have used the fuel that the Egyptians had prepared for themselves!” He was referring to the fuel depots that the Egyptians had placed alongside the roads in advance of their attack. “Why did Sharon and his division stop? They should have pressed on to Cairo!

- “To win a war,” the Rebbe persisted, “is to conquer the capital.”

Ceasefire

By October 9, the United States had begun pressuring Israel, Egypt, and Syria to commit to a ceasefire.[49]

In the early hours of October 22, while the IDF was in the process of encircling the Egyptian Third Army,[50] the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 338 which called for an immediate ceasefire and the start of peace negotiations.[51] Owing to a four-hour communications delay that prevented Israel from receiving timely notice of the resolution, Kissinger proposed that the ceasefire take effect 12 hours after its adoption to ensure that all parties were properly informed.[52]

The ceasefire officially began at 6:52 PM Israel time, but fighting soon resumed on the Sinai front.[53] In response, the Security Council adopted Resolution 340 on October 25, reaffirming its call for an immediate and complete ceasefire and the return of forces to their positions as of October 22.[54] While this resolution marked the formal end of the war, clashes persisted on both the Egyptian[55] and Syrian fronts for several months.[56]

In a public address delivered days after the ceasefire was implemented, the Rebbe asserted that Israel should have utilized the additional 12-hour window, suggesting that it was a deliberate opportunity extended by the United States:[57]

- Even when the U.S. finally decided to implement a ceasefire, they still stalled and allowed one more day—confident that Israel would have the sense to seize the moment. Damascus could still have been captured during that window. The same was true of the Arab forces still positioned on the eastern side of the Suez Canal.[58]

Other Mentions

Yom Kippur war same mistakes they regretted it for the rest of their life 13 Tammuz 574213 Tammuz 5742 video

YouTube: Preventing Futre Wars--Damascus, Cario and the Road to Peace, 1974

Making the same mistakes in Lebanon 19 Kislev 5743

If follow military will be less karbonus on both sides 19 Kislev 5743

They didn't need the weapons they decided to let jews die for the weapons 13 Tishrei 5739

Further Reading

References

- ↑ DIA Spot Report — October 6, 1973, 7:00 EDT; “Israel’s massive mobilization of 360,000 reservists upends lives.” Washington Post, October 10, 2023.

- ↑ “Slugfest on the Suez,” David T. Zabecki, HistoryNet (November 1, 2017); “Major General Recalls Fighting with Sharon in Yom Kippur War,” Jewish News, January 12, 2014; “Tank Clash in the Sinai,” Arnold Blumberg, Warfare History Network (March 2015); Saad el-Shazly, The Crossing of the Suez, Revised Edition (San Francisco: American Mideast Research, 2003), 228.

- ↑ Letter, 3 Elul, 5731. Igrot Kodesh vol. 27 p. 205.

- ↑ Gamal Hammad, Military Battles on the Egyptian Front (in Arabic) (First ed., Dar al-Shuruq, 2002), 667; “Israelis Prepare to Quit Last Post on Suez,” The New York Times, October 11, 1975.

- ↑ “Worse than the worst-case scenario: The dreadful hours before the Yom Kippur War,” Abraham Rabinovich, The Times of Israel, September 15, 2021. “In the Heat of Battle?” Abraham Rabinovich, The Jerusalem Post (March 22, 2007).

- ↑ The Hidden Calculation Behind the Yom Kippur War, Michael Doran, Hudson Institute (October 2, 2023); “I’m Not a Jew with Trembling Knees,” Steven Teplitsky, The Times of Israel, July 2, 2024; Saad el-Shazly, The Crossing of the Suez, Revised Edition (San Francisco: American Mideast Research, 2003), 228.

- ↑ 1973 Yom Kippur War — History Central; Assessing Israeli Military Effectiveness, Matthew F. Quinn (Monterey, CA: Naval Postgraduate School, December 2014), 13; The War for the Golan Heights, Abraham Rabinovich, Tablet Magazine (May 7, 2019).

- ↑ “The 1973 Yom Kippur War,” Uri Bar-Joseph (May 2009), Jewish Virtual Library; “Golda Meir’s Nightmare,” Amnon Barzilai, Haaretz, October 3, 2003.

- ↑ The Hidden Calculation Behind the Yom Kippur War, Michael Doran, Hudson Institute (October 2, 2023); Israel’s Survival at Stake, John E. Spindler, Warfare History Network (Summer 2023); “Golda Meir’s Nightmare,” Amnon Barzilai, Haaretz, October 3, 2003.

- ↑ “MIDDLE EAST: Black October: Old Enemies at War Again.” TIME, October 15, 1973; “Awe & Memory: The Yom Kippur War Forty Years Later.” Hadassah Magazine, October 13, 2013.

- ↑ The Rebbe maintained that a strong offensive and temporary occupation of enemy territory would dramatically shorten the war and save many lives (See “March on Enemy Capitals” below.)

- ↑ “Stop the Enemy! The Spiritual Battle of the Yom Kippur War,” A Chassidisher Derher 98 (175) (Tishrei 5781), 55. Shalom Yerushalmi, Yossi Elitov, and Aryeh Ehrlich, Berega Ha’emet [in Hebrew] (Modi’in, Israel: Dvir, 2017), 146–147.

- ↑ Abraham Rabinovich, The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter That Transformed the Middle East (New York: Schocken Books, 2004), 214; The Battle for the Golan Heights in the Yom Kippur War of 1973: A Battle Analysis, Benjamin Stanley Scott, Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects (2006), 24; The Fight for the Golan Heights, Morashá Institute of Culture, Edition 81 (August 2013). “The 1973 Yom Kippur War,” Uri Bar-Joseph (May 2009), Jewish Virtual Library; “Golda Meir’s Nightmare,” Amnon Barzilai, Haaretz, October 3, 2003.

- ↑ Although the Israeli Air Force had initially planned to strike Egyptian air defenses in the Sinai as part of Operation Tagar, the outbreak of a major Syrian offensive in the Golan Heights forced a sudden redirection of air assets to the northern front on the morning of October 7. The resulting air operation, Operation Doogman 5, was improvised under severe time pressure and with many key support elements—such as updated reconnaissance imagery, electronic warfare units, and decoy systems—either delayed or still deployed in Sinai, leading to significant losses in aircraft and crew. “Ma Bein ‘Tagar’ Le‘Dugman’ – Chelek Bet” [in Hebrew], Yossi Abudi, Merchav Aviri, December 12, 2008.

- ↑ “Tank Clash in the Sinai,” Arnold Blumberg, Warfare History Network (March 2015).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Address, 29 Cheshvan, 5734. Toras Menachem vol. 75 pp. 250-251; Shalom Dov Wolpo, Shalom Shalom Ve'ein Shalom, Vol. 2 [in Hebrew] (Kiryat Gat, 1982), 61.

- ↑ [Handwritten addition in the margins from the Rebbe. Such a strategy] brought full victory to the Germans over France in a few days.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Letter, 16 Cheshvan, 5734.

- ↑ Address, 13 Tishrei, 5734. Toras Menachem vol. p. 76; Likkutei Sichos vol. 14 p. 403; Audio.

- ↑ The 1973 Arab-Israeli War: The Albatross of Decisive Victory, Leavenworth Papers (1996), 55.

- ↑ Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881-1998, Benny Morris (Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 1999), 396.

- ↑ Negotiating the End of the Yom Kippur War — Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. “The 1973 Yom Kippur War,” Uri Bar-Joseph (May 2009), Jewish Virtual Library; “Golda Meir’s Nightmare,” Amnon Barzilai, Haaretz, October 3, 2003.

- ↑ The Hidden Calculation Behind the Yom Kippur War, Michael Doran, Hudson Institute (October 2, 2023); 1973 Yom Kippur War — History Central.

- ↑ Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness, 1948-1991, Kenneth Michael Pollack (University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 117.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 “Israel Sends a Task Force Behind the Egyptian Lines,” The New York Times, October 17, 1973.

- ↑ “Tank Clash in the Sinai,” Arnold Blumberg, Warfare History Network (March 2015); “Crossing Under Fire: The Israeli 143rd Armored Division at the Suez Canal, 1973,” Lieutenant Colonel Nathan A. Jennings (Marine Corps University Press, September 1, 2023).

- ↑ “Yom Kippur War: Embattled Israeli Bridgehead at Chinese Farm,” Christopher Robin Lew, HistoryNet (August 21, 2006); “Fighting with Agility: The 162nd Armored Division in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War,” Lt. Col. Nathan A. Jennings, Military Review (May-June 2023).

- ↑ The 1973 Arab-Israeli War: The Albatross of Decisive Victory, Leavenworth Papers (1996), 73; “Crossing Under Fire: The Israeli 143rd Armored Division at the Suez Canal, 1973,” Lieutenant Colonel Nathan A. Jennings (Marine Corps University Press, September 1, 2023). “The 1973 Yom Kippur War,” Uri Bar-Joseph (May 2009), Jewish Virtual Library; “Golda Meir’s Nightmare,” Amnon Barzilai, Haaretz, October 3, 2003.

- ↑ Kenneth W. Stein, Heroic Diplomacy: Sadat, Kissinger, Carter, Begin and the Quest for Arab-Israeli Peace (United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2002), 87; Michael K. Bohn, Nerve Center: Inside the White House Situation Room (United States: Brassey's, 2003), 74; U.S. DOS Middle East Task Force Situation Report #43 — Oct. 19, 1973; Kenneth W. Stein, Heroic Diplomacy: Sadat, Kissinger, Carter, Begin, and the Quest for Arab–Israeli Peace (London: Psychology Press, 1999), 87.

- ↑ Negotiating the End of the Yom Kippur War — Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training; “Damascus,” Aryeh Morgenstern — JEM.tv.

- ↑ See also address, 13 Tishrei, 5734. Toras Menachem vol. 74 pp. 81-82; Likkutei Sichos vol. 14 p. 408; Audio. Address, 17 Tishrei, 5734. Toras Menachem vol. 74 pp. 112-113; Likkutei Sichos vol. 14 p. 428. Letter, 3 Teves, 5741. Likkutei Sichos vol. 24 p. 452.

- ↑ Address, 1 Cheshvan, 5734. Toras Menachem vol. 74 p. 220; Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 p. 118; Diary, Sholom Dovber Shur.

- ↑ At the time, Syria served as a major sponsor of anti-Israel terrorism, providing support and backing to a range of terrorist organizations engaged in ongoing armed hostility against Israel. “Hafiz Asad and the Changing Patterns of Syrian Politics,” Malcolm H. Kerr, International Journal, Vol. 28, No. 4, The Arab States and Israel (Autumn, 1973), 690; “Der Konflikt zwischen Juden und Arabern als Etablierten-Außenseiter-Beziehung,” (in German) Peggy Klein, Diplom.de, (November 25, 1999), 53; “Syria: The First Arab on the Second Front.” TIME, December 8, 1975; Special National Intelligence Estimate — Office of the Historian “The Evolution of Islamic Terrorism: An Overview,” John Moore, FRONTLINE (PBS).

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 “Damascus,” Aryeh Morgenstern — JEM.tv. Diary, Sholom Dovber Shur; Shlomo Levin, Memorandum of visit to the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Oct. 22, 1973 — Jewish Educational Media Archive; Shalom Yerushalmi, Yossi Elitov, and Aryeh Ehrlich, Berega Ha’emet [in Hebrew] (Modi’in, Israel: Dvir, 2017), 175–178.

- ↑ Address, 19 Iyar, 5734. Toras Menachem vol. 76 pp. 142-143; Sichos Kodesh vol. 2 p. 106. Avraham Werdiger, Interview with My Encounter with the Rebbe Project, March 2001, Jewish Educational Media. Shalom Yerushalmi, Yossi Elitov, and Aryeh Ehrlich, Berega Ha’emet [in Hebrew] (Modi’in, Israel: Dvir, 2017), 182–183.

- ↑ Letter Zos Chanukah 5741, Kfar Chabad Magazine, Issue 1000.

- ↑ Sanhedrin 72a.

- ↑ Interview with Rabbi Elkanah Shmotkin, June 2020, Jewish Educational Media.

- ↑ See also address, 18 Elul, 5741. Sichos Kodesh vol. 4 p. 642; Video; Audio.

- ↑ Address, 1 Cheshvan, 5734. Toras Menachem vol. 74 p. 220; Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 p. 119.

- ↑ See “Memorandum of Conversation: Henry Kissinger Meeting with Jewish Leaders.” June 15, 1975: “What we wanted was the most massive Arab defeat possible so that it would be clear to the Arabs that they would get nowhere with dependence on the Soviets.”

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 “Damascus,” Aryeh Morgenstern — JEM.tv.

- ↑ In the immediate aftermath of the Six Day War, the government had decided to return the territories liberated in the Six Day War and asked Washington to pass on the message to Egypt and Syria. Chaim Herzog, Heroes of Israel: Profiles of Jewish Courage (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1989).

- ↑ Address, 1 Cheshvan, 5734. Toras Menachem vol. 74 p. 221; Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 p. 118.

- ↑ “Kissinger was also encouraging Israel to move towards the Syrian capital in order to give it more muscle at the negotiating table.” Abraham Rabinovich, The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter That Transformed the Middle East (New York: Schocken Books, 2004), 259.

- ↑ Abraham Rabinovich, The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter That Transformed the Middle East (New York: Schocken Books, 2004), 259.

- ↑ Address, 19 Iyar, 5734. Toras Menachem vol. 76 p. 143; Sichos Kodesh vol. 2 p. 106.

- ↑ Avraham Werdiger, Interview with My Encounter with the Rebbe Project, March 2001, Jewish Educational Media. Shalom Yerushalmi, Yossi Elitov, and Aryeh Ehrlich, Berega Ha’emet [in Hebrew] (Modi’in, Israel: Dvir, 2017), 182–183.

- ↑ William Quandt, Peace Process: American Diplomacy and the Arab–Israeli Conflict Since 1967 (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution / University of California Press, 2005), 110–111.

- ↑ “Crossing Under Fire: The Israeli 143rd Armored Division at the Suez Canal, 1973,” Lieutenant Colonel Nathan A. Jennings (Marine Corps University Press, September 1, 2023), pp. 71-73.

- ↑ UNSC Resolution 338.

- ↑ “Kissinger Gave Israel Tacit Approval.” Global Policy Forum, October 9, 2003.

- ↑ Abraham Rabinovich, The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter That Transformed the Middle East (New York: Schocken Books, 2004), 452; “A Self-Inflicted Wound? Henry Kissinger and the Ending of the October 1973 Arab-Israeli War,” Galen Jackson and Marc Trachtenberg, Journal of Cold War Studies, (2021), 14.

- ↑ The 1973 Arab-Israeli War — Office of the Historian; UNSC Resolution 340.

- ↑ U.S. DOS Middle East Task Force Situation Report #66 — Oct. 26, 1973; Moshe Dayan, Story of My Life (New York: Da Capo, 1992), 568.

- ↑ “Hatasha BaTzafon: Milchamat HaHatasha Mul Suriya Bein Hafsakat HaEsh LeVein Hafradat HaKochot, 1973–1974” [in Hebrew], Ran Shamai, (July 5, 2023); “Yom Kippur A Quiet Day In the Golan.” New York Times, September 27, 1974.

- ↑ See “Memorandum of Conversation: Henry Kissinger Meeting with Jewish Leaders.” June 15, 1975: “We didn’t go to Moscow to cave. We wanted to delay the Security Council in order to give Israel 72 more hours to fight. Going to Moscow was our way to give Israel more time.”

- ↑ Address, 1 Cheshvan, 5734. Toras Menachem vol. 74 p. 221; Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 pp. 119.