Preemptive Defense

Overview

Torah’s approach to defense is predicated on the fundamental principle that human life is of supreme value, rendering the protection of life an obligation, rather than a right. Jewish law emphasizes the necessity of proactive and decisive defensive measures, including the exercise of appropriate force to neutralize or deter an adversary before harm is inflicted. The supremacy of this obligation overrides all other considerations, including potential diplomatic or political implications.

Adhering to this principle not only ensures the protection of potential victims, but will also prevent loss of life on the side of the adversary. Proactive defense creates conditions for enduring peace and security for all parties in the conflict.

Provenance

Torah places the preservation of human life (pikuach nefesh) as its highest priority. With the exception of three cardinal prohibitions,[1] all commandments—both positive commandments and prohibitions—are suspended when there is a potential risk to human life.[2]

While this principle may appear self-evident, it establishes a distinctive hierarchy of values that differs from alternative ethical frameworks that prioritize other considerations such as political autonomy, procedural justice, human rights, or pacifism, irrespective of consequences.

Torah’s placement of the protection of human life as an objective of the highest order, in turn, informs its approach to defensive action, in which eliminating threats to human life maintains the highest priority. In the words of the Talmud:

- “If someone is coming to kill you, rise early to kill them first.”[3]

The biblical source of this principle is in the laws concerning a thief. “If a thief is caught while breaking in and is struck and killed, there is no liability for his blood.”[4] The Talmud explains the reasoning: The baseline assumption is that an intruder anticipates the homeowner will attempt to defend their property, and the intruder is prepared to kill if confronted. By proceeding with the burglary, the thief demonstrates a willingness to commit murder to achieve their objective, rendering them a lethal threat.[5]

Such a person is classified as a “pursuer” (rodef) by Jewish law, one who poses an immediate threat to the life of another. Jewish law obligates intervention to prevent loss of life, even if such intervention entails the use of lethal force against the pursuer.[6] The homeowner—or even a third party—is required to act preemptively to neutralize the threat.

Present Day Application

Applying this rule to Israel’s national defense, the Rebbe taught that by Torah’s directive, Israel is not permitted to wait passively and reactively defend itself only once attacked. Instead, he maintained that Israel must adopt a proactive defensive strategy consisting of three key elements: (a) preemptive action against imminent threats, (b) sustained deterrence to prevent adversaries from initiating conflict and (c) neutralization of developing enemy capabilities before they mature into operational dangers.

Decisive Defense

In the event of an imminent security threat, immediate and decisive military action must be taken to neutralize it. Tangible threats must be met with a direct and forceful physical response.

- Once you are aware of the threat, Torah instructs you: “Rise early to kill him first.” Don’t wait until he attacks—that may be too late, G-d forbid. Rather, take preemptive action.[7]

Following the Six-Day War, military hostilities persisted along the Suez Canal between Israel and Egypt, eventually escalating into the War of Attrition. During this period, Israel frequently turned to the United Nations, requesting its intervention to halt Egypt’s aggression.[8] In an address on Purim, March 4, 1969, the Rebbe strongly criticized this strategy:

- When you are aware that someone is out to murder you, the solution is not to sit around and wait for every other nation to endorse your actions, or for all of the representatives at the UN to cast their votes to decide whether or not you have the right to retaliate. This is not how to address someone who is intent on murder.

- The Talmud presents a very rational idea, it need not be accepted on faith. When someone is coming to kill you, it is not a time to lodge complaints. He must see that you “rise early to kill him.”[9]

In the hours leading up to the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War on October 6, 1973, Israel’s intelligence services had confirmed that a coordinated Egyptian-Syrian attack was imminent. Despite this, Prime Minister Golda Meir chose not to authorize a preemptive strike. U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had cautioned that if Israel fired the first shot, it risked being perceived as the aggressor and jeopardizing American support. This decision led to initial setbacks, substantial territorial losses, and significant casualties.[10]

In a public address on November 19, 1977, and on many other occasions, the Rebbe sharply criticized this decision, arguing that a preemptive strike would have been both militarily and strategically advantageous, and would have led to a swift victory:

- If Israel had launched a preemptive strike even just a few hours earlier, when it became clear that the enemy was preparing to attack—there would have been no war by the ninth day! The war would have been won much sooner, similar to the swift victory in the Six-Day War, and perhaps even more quickly [. . .]

Responding to concerns that such an action might have been perceived as as act of aggression, the Rebbe argued that a strike of such nature was, by definition, a form of self-defense:

- The argument against launching a strike holds no ground, because when the opposing side is already prepared to attack, a strike against them is not “aggression” but rather a preemptive war—an act of self defense, fulfilling the principle of “If someone comes to kill you, rise early to kill them first.”[13]

Deterrence

The Rebbe taught that a key aspect of Israel’s security was deterrence—demonstrating strength and readiness, so that enemies are dissuaded from attacking, thus preventing conflict and the loss of life. Highlighting a subtle, yet crucial, distinction in the Talmud’s text, the Rebbe explained:

- The Talmud states “If someone comes to kill you, rise early to kill him first,” It doesn’t say you must actually kill him—it needn’t reach that point. When the enemy sees that you have arisen at dawn with a display of force, ready to act if necessary—that if they choose to strike, you will be prepared to do so first—then they won't attack in the first place.[14]

A core element of establishing deterrence is maintaining a strong military edge. In an address attended by Israeli officials involved in arms procurement, the Rebbe explained that “amassing arms does not increase the likelihood of war—quite the opposite.” The purpose of obtaining a qualitative and large quantity of weapons is to “instill fear in potential aggressors, and thereby avoid conflict entirely.”[15]

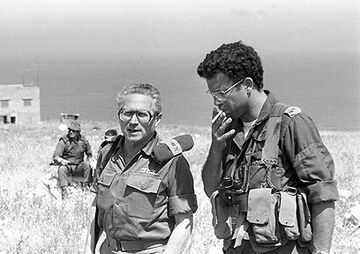

On May 8, 1988, during a conversation with Yossi Ben Chanan, Commander of the Israeli Armored Corps, the Rebbe blessed its soldiers:

May the security be achieved through being so strong that enemies will be afraid to even consider hostility towards Israel. This is the greatest victory: when there is no need to fight in the first place... You already have the strength [for this]; you need only to utilize it. To have power that is hidden away, guarded so carefully that no one knows of it, defeats its entire purpose.

The Rebbe also applied this principle of deterrence to the terrorist threat Israel faces. In a private audience in late 1969 with Yossi Ciechanover, General Counsel to Israel’s Ministry of Defense, the Rebbe emphasized the need for Israel to adopt a consistent zero-tolerance policy toward both terrorists and those who harbor them. He cautioned that allowing terrorism to fester and permitting strongholds of terrorism to develop only serves to encourage broader participation. “The reduction of terrorism is ultimately beneficial for the entire population,” the Rebbe stated.[16]

On May 2, 1980, six Jews were killed and twenty others wounded in a terrorist ambush as they returned from Shabbat evening prayers at the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron. The assailants were later identified as members of a PLO-directed cell and were apprehended several months later.[17]

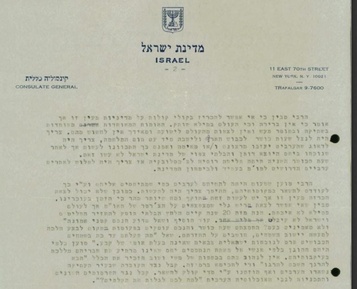

In a December letter to Mr. Pinchus Meir Kalms, the Rebbe recounted his response to the attack and the Israeli government's handling of it, indicative of his broader stance on the appropriate response to terrorism and the necessity of deterrent action.

- It is known that there were two schools of thought in the government on this issue. One held that it would be expedient not to press the hunt for the killers on the ground that to find and put them on trial, etc. would exacerbate tensions; therefore, it would be better to put the matter at rest by procrastination. The other held that the Government should take all possible action to apprehend the killers and punish them swiftly, not only because “the blood of our brethren cries out to us from the earth,”[18] but also, and just as importantly, for pikuach-nefesh [life-saving] reasons, to prevent further similar attacks. For, anyone who knows the mentality of those Arab circles from which the terrorists came, knows that failure to punish them would be interpreted as a sign of weakness and be an encouragement to repeat such attacks.

- This debate went on for weeks. When I saw that inaction was the government’s policy and that it would be a serious blow to pikuach-nefesh [the safety of lives], I made my public statement. Fortunately, it had an impact and finally the hunt began in earnest, resulting in the speedy apprehension of the leader of the gang. Parenthetically, the sad epilogue of this chapter, which is in itself a reflection of the state of affairs in [Israel], is that although many weeks have passed since the murderer was caught, he has not as yet been put on trial and there is still no word as to when this will come to pass. No further commentaries are necessary.[19]

On October 3, 1968, Rehavam Amir, Israel’s Consul General to the United States, and Zvi Caspi, Consul for Jewish Affairs, met with the Rebbe. During the meeting, the Rebbe criticized Israel’s handling of captured terrorists, arguing that the existing policy failed to deter their comrades from continuing their attacks. He warned:

- It is a mistake that you leave the captured terrorists in prison. These terrorists had come with the intent to kill and, “If someone comes to kill you, rise early to kill them first.” You will pay a high price for imprisoning them, as in the future you will be met with demands for release and prisoner swaps.[20]

On December 15, 1985, in response to the recent increase in terrorism in Israel,[21] the Rebbe addressed this issue again, highlighting the failure of the Israeli prison system to deter terrorists from committing further attacks:

- No terrorist fears the “punishment” of serving time in an Israeli prison—quite the opposite. There, they receive all their needs: food, drink, shelter, and more, readily provided—far better than in their own villages. Moreover, before long, a “prisoner exchange deal” will take place, securing their release, along with hundreds of other terrorists like them, in exchange for three to five Jews—just as has happened in the past, and has now become routine.[22]

Avoiding Vulnerability

The Rebbe believed that Israel’s obligation to defend itself is not limited to responding to threats once they emerge. Rather, he maintained that Israel is obligated to ensure it never reaches a point of vulnerability by eliminating potential dangers—before they pose an immediate threat. Preventing such scenarios, he argued, is itself a core tenet of national security according to Torah law.

During his 1968 meeting with Rehavam Amir and Zvi Caspi, in the aftermath of the Six-Day War, the Rebbe outlined how this principle applied to the contemporary geopolitical landscape. Following the meeting, Caspi documented the main points of their discussion:[23]

- The Rebbe asserted that the Arabs were united in their intent to rise against Israel, sooner or later, and therefore we are commanded to act according to the principle, “If someone comes to kill you, rise early to kill him first.” He explained that this directive did not apply solely to situations where the exact time of the attack was known, but once there was knowledge of an enemy’s intent to harm.

- He further explained that “rise early to kill them” also means being prepared and properly equipped to confront such threats effectively.[24]

During the War of Attrition, as hostilities persisted along the Suez Canal, Israel refrained from launching decisive preemptive strikes or establishing a clear deterrence posture, opting instead for a strategy of limited responses while pursuing diplomatic channels in an effort to de-escalate the conflict. The protracted conflict resulted in over 1,400 Israeli casualties.[8][25]

On August 7, 1970, both nations agreed to a temporary ceasefire, which included a standstill provision prohibiting the construction of new military installations.[26]

During the negotiations leading up to the ceasefire, the Rebbe warned against the Israeli government accepting the agreement, arguing that it would allow Egypt to reinforce its military positions along the Suez Canal and thereby undermine Israel’s strategic advantage:

- Egypt’s sole motive for seeking a ninety-day ceasefire is to gain time to construct new fortifications along the Suez Canal, and to stockpile them with new weapons—which are already prepared and waiting in Libya, France, or Russia, awaiting the opportunity to be transferred to the front lines. At present, they cannot transfer the materials due to the non-stop shelling by Israel over the past three months—specifically intended to prevent the construction of fortifications and the delivery of weapons. So they need a ninety-day suspension of hostilities, and they already have a pretext as to why they won’t honor the terms of the standstill agreement.[27]

Indeed, minutes after the ceasefire began, Egypt began to violate the standstill agreement by deploying missiles and fortifying its positions along the Suez Canal.[28]

In a public address two weeks after the ceasefire went into effect, the Rebbe proclaimed that Israel was obligated to carry out “the only logical response—bombing and destroying the equipment, missiles, and fortifications the Egyptians had constructed,” to remove them as a means of lethal force against Israel’s front-line troops.[29]

In subsequent years, diplomatic efforts to achieve peace between Israel and Egypt were unproductive. Meanwhile, Egypt continued to bolster its military capabilities unimpeded, particularly along the Suez Canal. The deployment of surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems in the region provided Egypt with substantial air defense cover that played a crucial role in its surprise attack on Israel at the start of the Yom Kippur War, in October of 1973. The SAMs significantly impeded the operational effectiveness of the Israeli Air Force, leading to heavy IAF and IDF losses.[30]

Human Life On All Sides

The Rebbe maintained that adopting an effective, proactive defense strategy would not only ensure Israel’s security but also preserve lives on the opposing side—a moral obligation he described as “the most important duty of a human being . . . to protect the lives of non-Jews, as well—for they, too, were created in God’s image.”[31] In his address on Purim, March 4, 1969, he said:

- [Proactive defense] is, in fact, in the best interest of the enemy, as well. If you truly seek his well-being—to avoid war and preserve his life—this is the only approach that will make him take you seriously![32]

Diplomatic Considerations

The principle of prioritizing security remains paramount, even in the face of political, economic, or international pressures. According to the Torah, Jews—and by extension, the Jewish state—may never compromise its security or expose itself to vulnerability in exchange for promises, agreements, or concessions of any kind. Ensuring physical safety takes precedence over potential diplomatic or economic gains.

He referenced the oft-suggested approach of resolving conflicts through diplomatic engagement and dialogue. Highlighting the attempts to reason with aggressors intent on violence, the Rebbe wryly pointed to the futility of the approach Israel had been adapting:

- [Israel approaches its neighboring aggressor states and declares]: “Excuse me, Mister Cossack, inasmuch as you wish to kill Jews, you should be aware that this violates the UN Charter! You must first call a meeting and request permission. True, you attacked yesterday without permission—it's too late for that—but you can change your ways from now on!”

- You can lodge complaints, send delegates, and engage in endless talk—all of which have been tried, at the expense of so many lives. Not only did these methods fail to remedy the situation, they exacerbated it. The enemy sees that they can strike as often as they’d like with impunity.[33]

Even when such decisions appeared to conflict with potential security interests, the Rebbe emphasized that such calculations should not influence Israel’s actions:

- Although Israel finds itself in a situation where it needs resources—whether money, weapons, or advice—from foreign sources, [. . .] when it comes to its national defense, no external pressure may influence its decisions. Israel must stand firm, confident that by doing so, it will not only avoid negative outcomes but, in fact, strengthen its position and earn respect for the Jewish people on the international stage.[34]

Historical Examples

On June 5, 1967, Israel launched Operation Focus (Moked), a preemptive airstrike targeting the Egyptian Air Force. This operation resulted in the destruction of approximately 90% of Egypt's air power, effectively neutralizing its aerial capabilities. Israel launched a similar air assault against the Syrian air bases, severely hindering its capabilities. The success of this decisive action enabled Israel to gain air superiority, facilitating rapid ground offensives that led to the capture of the Sinai Peninsula, Gaza Strip, and Golan Heights.[35]

The War of Attrition was a protracted conflict between Israel and Egypt fought along the Suez Canal from 1969 to 1970, characterized by limited artillery duels, airstrikes, and commando raids. Israel avoided launching a major offensive, opting instead for measured retaliatory actions while pursuing diplomatic channels. Egypt, meanwhile, continued its campaign of attrition largely undeterred. The conflict resulted in the deaths of over 1,400 Israeli soldiers and thousands of Egyptian casualties.[8][25][36]

The Rebbe sharply criticized Israel’s restrained approach, arguing that its limited military responses failed to deter continued Egyptian aggression and prolonged the conflict. He advocated for a decisive military response that would have ended the war sooner and saved lives.[37]

On October 6, 1973, during Yom Kippur, Egypt and Syria launched a coordinated surprise attack against Israel. Despite prior intelligence informing them of the attack, Israel’s leaders aimed to avoid the appearance of aggression, choosing not to initiate preemptive military action. This decision led to initial setbacks, substantial territorial losses, and significant casualties.[38]

The Rebbe was highly critical of this decision, arguing that a preemptive strike would have significantly shortened the conflict and prevented unnecessary loss of life.[39]

Following a deadly terrorist attack on March 11, 1978—in which PLO terrorists infiltrated from Lebanon and killed 38 Israeli civilians—Israel launched Operation Litani, swiftly capturing most of southern Lebanon up to the Litani River in an effort to drive the PLO beyond it.[40] However, under mounting international pressure, Israel declared a ceasefire by March 21 and began a gradual withdrawal, despite the operation’s failure to achieve its objectives. Control of the region was transferred to the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) and the South Lebanon Army (SLA).[41]

The Rebbe praised the initial phase of the operation for its decisiveness and reliance on military expertise rather than political bureaucracy.[42] However, he strongly criticized Israel’s subsequent withdrawal and the handover of security to international forces, viewing the move as a strategic failure that would embolden terrorism and undermine Israel’s long-term national security.[43]

In the wake of the withdrawal, the PLO quickly reestablished its presence in in the area, leading Israel to rely on the South Lebanon Army and intermittent airstrikes by the Israeli Air Force to contain the threat. Persistent hostilities and the continued resurgence of PLO activity ultimately led to the outbreak of the First Lebanon War in 1982.[44]

Operation Opera (1981)

On June 7, 1981, Israel conducted a surprise airstrike that destroyed the Osirak nuclear reactor located approximately 18 kilometers southeast of Baghdad, Iraq. At the time, the international community, including the United States, sharply criticized the attack, viewing the strike as a violation of Iraqi sovereignty. The United Nations Security Council unanimously passed Resolution 487, condemning Israel’s actions.[45] Despite the loud condemnation, Israel suffered precious little in the way of concrete repercussions.

In retrospect, the operation was credited with preventing Saddam Hussein’s regime from acquiring nuclear weapons capabilities, protecting Israel and other western countries from a hostile nuclear threat. Captured documents from conversations between Saddam Hussein and his inner circle reveal that in a 1982 discussion, Hussein stated, “Once Iraq walks out victorious [over Iran], there will not be any Israel.” He also acknowledged Israel’s strategic reasoning, noting, “Technically, they [the Israelis] are right in all of their attempts to harm Iraq.”[46]

In 1991, despite its initial outrage, the United States was thankful for Israel’s actions. According to U.S. Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney, “There were many times during the course of the build-up in the Gulf and the subsequent conflict that I gave thanks for the bold and dramatic action that had been taken some ten years before.”[47]

Operation Orchard (2007)

On September 6, 2007, Israel executed an airstrike targeting a suspected nuclear reactor at Al Kibar in Syria's Deir ez-Zor region. The facility was believed to be a clandestine nuclear reactor under construction with North Korean assistance.

Although initially met with skepticism regarding its status as a nuclear reactor, the facility was officially confirmed by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in 2011 as a covert nuclear reactor under construction.[48]

Upon the fall of Syria to radical islamists in early 2025, that attack turned out to be prescient.

Other Mentions

Further Reading

19 Kislev, 5734 – Although life and death is in the hands of G-d, He wants our defense to come about in a natural way (Sichos Kodesh vol 1 pp. 145-146)

The Rebbe contrasted Torah’s stance on the importance of decisive defensive action as the truest means to achieve enduring peace, with moral arguments that Israeli military action is unjustifiable, in almost any instance:

The [other nations] say, “You want to retaliate? Where is your sense of justice and morality?! How could you do such a thing?

“First, bring the case before the UN, where all the upstanding, moral members will gather, having first been at their places of worship, where they were taught to ‘love your fellow as yourself,’ and that when struck on one cheek, you must ‘turn the other cheek.’

“Then, they will decide the status of the attacker, and you will oblige and follow their instructions…”

Torah teaches: “No. This is not the way.”[49]

References

- ↑ Namely: murder, adultery, and idol worship (see source in the next footnote).

- ↑ Sanhedrin 74a; Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Yesodei Hatorah 5:2.

- ↑ Brachos, 62b.

- ↑ Exodus 22:1.

- ↑ Sanhedrin 72a.

- ↑ Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Rotzeach 1:6-9

- ↑ Address, 27 Tishrei, 5729. Toras Menachem vol. 54 p. 242; Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 p. 95.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Question of Palestine — Yearbook of the United Nations 1969 (excerpts).

- ↑ Address, Purim 5729. Toras Menachem vol. 55 p. 357; Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 p. 436; Video, Audio.

- ↑ “Kissinger's triumph began in trauma.” New York Times, June 23, 1974; Abraham Rabinovich, The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter That Transformed the Middle East (New York: Schocken Books. 2004), 89.

- ↑ Sanhedrin 37a.

- ↑ Address, 9 Kislev, 5738. Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 p. 228; Audio.

- ↑ Address, 9 Kislev, 5738. Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 p. 227; Audio.

- ↑ Address, Purim 5729. Toras Menachem vol. 55 p. 363; Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 p. 441; Video, Audio.

- ↑ Address, 10 Shevat, 5735. Toras Menachem vol. 79 p. 134; Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 p. 334; Video, Audio.

- ↑ Shmotkin-Moscowitz Teshura, 16 Elul, 5784; “The Rebbe’s Diplomat: Joseph Ciechanover’s Hidden Role in Israeli History.” Chabad.org, January 7, 2025.

- ↑ “Palestinian terrorist in killing of 6 Jews elected Hebron mayor.” Times of Israel, May 14, 2017; “Israel Charges 10 Palestinians in Hebron Ambush.” Washington Post, September 17, 1980.

- ↑ Cf. Genesis 4:10.

- ↑ Letter, Third Light of Chanukah, 5741, pp. 3-4.

- ↑ Yitzchak Yehudah, Kfar Chabad issue 1637, p. 38.

- ↑ Repertoire of the Practice of the UN Security Council, 1985–1988, p. 283; The Year in Review, 1985 — cia.gov.

- ↑ Address 3 Tevet, 5746. Toras Menachem vol. 2 p. 233; Sichos Kodesh; Video, Audio.

- ↑ This document was sent on October 16, 1968, to Yaakov Herzog, an adviser to Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and head of the American desk at the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Aharon Dov Halperin, Yechidiot vol. 4 (Israel, 2020), 149; Yitzchak Yehudah, Kfar Chabad issue 1637, p. 38; Weekly Moment With the Rebbe.

- ↑ See image.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 “The War of Attrition 50 Years On.” The Times of Israel, March 2, 2019; The War of Attrition: Background & Overview.

- ↑ Israel-Egypt Ceasefire Agreement (1970) - Text.

- ↑ Address, 28 Tammuz, 5730. Toras Menachem vol. 61 p. 109; Sichos Kodesh vol. 2 p. 433.

- ↑ Arab-Israeli Ceasefire of 1970 – cia.gov; “Dayan Urges U.S. to Compel Egypt to Respect Truce.” The New York Times, August 14, 1970; “Mideast Cease-Fire.” The New York Times, August 22, 1970.

- ↑ Address, 20 Av, 5730. Toras Menachem vol. 61 p. 159. Sichos Kodesh vol. 2 p. 460b.

- ↑ Myths & Facts The War of Attrition and the Yom Kippur War.

- ↑ Address, 3 Tammuz, 5742. Toras Menachem vol. 3 p. 1722; Audio.

- ↑ Purim 5729. Toras Menachem vol. 55 p. 363; Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 p. 441; Video, Audio.

- ↑ Address, Purim 5729. Toras Menachem vol. 55 p. 358; Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 p. 437; Video, Audio.

- ↑ Address, 9 Kislev, 5738. Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 p. 225; Audio.

- ↑ Six-Day War - Britannica.

- ↑ War of Attrition – Britannica.

- ↑ Address, Purim 5729. Toras Menachem vol. 55 p. 359; Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 p. 438; Video; Audio.

- ↑ “Kissinger's triumph began in trauma.” New York Times, June 23, 1974; Abraham Rabinovich, The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter That Transformed the Middle East (New York: Schocken Books. 2004), 89.

- ↑ Address, 9 Kislev, 5738. Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 p. 227; Audio.

- ↑ Statement by Prime Minister Begin – 12 March 1978; Coastal Road Massacre Takes Place — Center for Israel Education; "7 Weeks Later, the Israelis Debate Benefits and Losses From the Invasion of Lebanon." New York Times, May 7, 1978; "Israelis Push Deeper Into Lebanon." New York Times, March 20, 1978; Operation Litani.

- ↑ United Nations Security Council Resolution 425-426 (text); "Israeli Troops Start First Phase Of Withdrawal in South Lebanon." New York Times, April 12, 1978; "Israelis Withdraw Last Invasion Units in Southern Lebanon." New York Times, June 14, 1978; "Israelis will leave, Begin promises U.N." Press-Republican, March 25, 1978; Israel and the Army of South Lebanon — cia.gov; Ferdinand Smit, The Battle for South Lebanon: Radicalisation of Lebanon's Shi'ites 1982–1985 (Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Bulaaq, 2006), 115.

- ↑ Address, Purim, 5738. Sichos Kodesh vol. 2 p. 27; Audio.

- ↑ Address, 14 Iyar, 5738. Sichos Kodesh vol. 2 pp. 288-289; Audio.

- ↑ Ferdinand Smit, The Battle for South Lebanon: Radicalisation of Lebanon's Shi'ites 1982–1985 (Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Bulaaq, 2006), 115; Israel and the Army of South Lebanon — cia.gov; Report of the Secretary General on UNIFIL, June 15, 1981; Zeev Maoz, Defending the Holy Land: A Critical Analysis of Israel's Security and Foreign Policy (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2006), 181.

- ↑ “The Bush doctrine makes nonsense of the UN charter.” The Guardian, June 6, 2002; United Nations Security Council Resolution 487 (Text).

- ↑ Davos Annual Meeting 2005 - Bill Clinton; “Iraq Archive Reveals Saddam Hussein’s Conspiratorial Mind-Set.” New York Times, Oct. 25, 2011.

- ↑ “Cheney to Israel: Thanks for destroying Iraqi reactor; Will U.S. take 10 years to accept Israeli stance on peace?” Center for Security Policy, October 30, 1991.

- ↑ “Syria Rebuilds on Site Destroyed by Israeli Bombs.” New York Times, January 12, 2008; “Will Syrian site mystery be solved?” BBC News, 23 June, 2008; “Syria target hit by Israel was ‘nuclear site’ | Environment News.” Al Jazeera, April 29, 2011.

- ↑ Address, Purim 5729. Toras Menachem vol. 55 p. 358; Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 p. 437; Video, Audio.