Sinai Interim Agreement - 1975

Overview

The Sinai Interim Agreement, signed in September 1975, followed the Yom Kippur War of October 1973, and was an early step in the peace talks between Israel and Egypt. Under the terms of the agreement, Israel agreed to withdraw from strategic locations in the Sinai Peninsula, including key oil fields and passes. This arrangement aimed to reduce hostilities and set the stage for future peace talks.

The Rebbe expressed deep concerns about the security risks posed by the agreement. Challenging the territorial concessions, he believed they would weaken Israel's defense capabilities and strategic depth. He questioned Egypt’s reliability in adhering to the terms, citing past violations, and warned that such concessions could set a dangerous precedent, encouraging other nations to pursue military aggression with the expectation of gaining territory through subsequent negotiations.

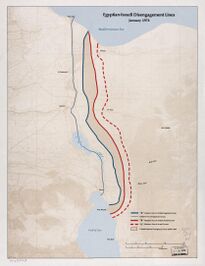

Israel-Egypt Disengagement Agreement

During the Six-Day War in June 1967, Israel captured Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. Hostilities between the two nations persisted for the following three years, eventually escalating into the War of Attrition (1969–1970), an unsuccessful attempt by Egypt to reclaim the Sinai through sustained military pressure.

In October 1973, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat launched the Yom Kippur War, aiming to regain lost territories by compelling Israel to negotiate under more favorable terms for Arab nations.[1]

Following the Yom Kippur War, the United States intensified pressure on Israel to negotiate a peace agreement with Egypt, with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger leading these diplomatic efforts. This led to the Israel-Egypt Disengagement Agreement in January 1974 (also referred to as Sinai I). Under the terms of this agreement, Israel agreed to withdraw from territories along the Suez Canal, establishing a UN-monitored buffer zone between Israeli and Egyptian forces.[2]

Negotiations

With the successful implementation of the disengagement agreement, Kissinger embarked on a new phase of shuttle diplomacy aimed at achieving a more comprehensive peace agreement.[3] Throughout late 1974 and into 1975, the US leveraged its military aid to Israel, using the provision of essential arms as a means to press Israel into making progress in negotiations with Egypt.[4]

On January 22, 1975, the Rebbe led a large gathering marking the 25th anniversary of the passing of his father-in-law and predecessor, and his own leadership of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement. The event was attended by representatives of President Gerald Ford, New York Governor Hugh Carey, and other government officials.

In his address, the Rebbe expressed gratitude to the United States government for its steadfast military and economic support of Israel, and expressed his hope that it would continue in the future. He emphasized that the primary function of advanced weaponry was not to wage war but to serve as a strong military deterrent. The Rebbe asserted that it was in the United States’ best interest to ensure Israel had the necessary arms for self-defense, noting that, as a superpower, the US understood that a Middle Eastern war could potentially involve the entire globe. Therefore, adequately arming Israel could help avert conflict altogether.[5]

During the event, Joseph “Yossi” Ciechanover, who had been tasked with establishing an Israeli defense mission in the United States to manage and finance weapons procurement, approached the Rebbe for a private conversation. When Ciechanover expressed his concerns about the ongoing discussions with the US regarding Israel’s arms request, the Rebbe reassured him that the US would provide the necessary support and offered strategic advice on proceeding with the discussions with Secretary of State Kissinger.[6]

In subsequent months, the US continued to exert significant pressure on Israel to advance the peace negotiations.[7] On March 21, President Ford conveyed in a letter to Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin his “profound disappointment over Israel’s attitude in the course of the negotiations,” adding that he had “given instructions for a reassessment of [. . .] our relations with Israel” due to the “failure of the negotiation.”[8]

In the wake of this letter, the US slowed arms deliveries to Israel and declined to provide a long-term commitment of aid. However, this policy shift faced strong opposition from Congress, ultimately leading President Ford to reverse the reassessment by early summer.[9]

Sinai Interim Agreement

By September 1975, Israel and Egypt reached a significant accord known as the Sinai Interim Agreement (also referred to as Sinai II). Under this agreement, Israel committed to withdrawing from key strategic locations in the western Sinai Peninsula, including the Mitla and Gidi Passes, as well as the Abu Rudeis and Ras Sudar oil fields along the western coast.

This arrangement enabled Egypt to regain control over these areas, with a United Nations-monitored buffer zone established to separate the military forces. In exchange, both nations promised to end armed hostilities and to limit their arms and military forces near the border.

The accord was officially signed on September 4, 1975, in Geneva, Switzerland.[10]

Shortly thereafter, Brigadier General Ran Ronen-Pecker met with the Rebbe. Pecker later recalled:

- We spoke about the Sinai Interim Agreement, which Israel had just signed [. . .] The Rebbe criticized this very sharply: “You don’t hand away natural resources. These are assets! Oil and strategic territory you just don’t give away. It is wrong.”

- He argued that only military commanders should determine what can and can’t be returned. The politicians don’t understand security matters as well and, therefore, they have no right to decide what land to return. They are not the ones who will have to fight for it again. [. . .] He criticized the treaty very strongly. He just couldn’t get over the fact that we made concessions which were unnecessary and unjustified. “Have you ever heard anything like this?” he asked. “A country is victorious, and it proposes that its enemies take the territories back?”[11]

In a public address on November 23, the Rebbe expressed deep concerns regarding the accord’s security implications for Israel, and whether it could lead to an enduring peace. He articulated a detailed critique of the dangers of the territorial concessions:

- This agreement required Israeli forces to withdraw from secure borders—borders that, not long before, were declared by Israeli officials to be the only boundaries that can truly assure Israel’s security.[12] Additionally, the agreement mandated handing over to Egypt vital oil fields—resources that enable tanks to move and planes to fly—and a strategically advantageous fortified location, which, while not entirely secure, was still superior to the flat terrain [which make up the areas Israel currently holds in the Sinai].

- Military experts were consulted on this matter, and all of them unanimously stated that withdrawing from the Suez Canal, the Mitla Pass, the Gidi Pass, and surrendering the oil fields would place the lives of IDF soldiers in tangible danger. There is simply no safer defensive position available. As for oil, there is no alternative source. While one could theoretically appeal to Washington, it is well-known that the president is not particularly fond of Israel, as evidenced in the events of just six months ago.[13]

Drawing on past experience, the Rebbe questioned the logic of trusting Egypt to uphold the terms of the agreement. He cited the ceasefire of the War of Attrition as a cautionary example: within minutes of that ceasefire, Egypt had violated the standstill agreement by advancing missiles and weaponry towards the Suez Canal.[14] He argued that such precedents made it highly likely that Egypt would breach this new agreement as well.

The Rebbe underscored that the danger posed by this agreement was far greater than that of previous arrangements. By surrendering control of both the Suez Canal and vital oil fields, Israel was relinquishing not only territories that provided strategic depth essential for its defense but was also setting itself up for total dependence on other nations for its energy needs—something that could be exploited in the future. The likelihood of Egypt violating the agreement—combined with Israel’s weakened positions—constituted a far graver risk than past scenarios.

Additionally, the Rebbe argued that negotiating with Egypt and offering territorial concessions as an outcome of its attack on Israel in the Yom Kippur War was a dangerous precedent. By offering tangible concessions to a nation that had recently waged war on Israel, Israel was setting an example that would encourage other countries to pursue similar actions:

- Israel initially addressed the territorial demands of only Egypt. However, it later realized that it must contend with the demands of the other neighboring countries. After all, if negotiations would be held with only one or two countries, the others would likely want their own share of territory as well. It is almost certain that these adversaries will do everything in their power to disrupt the peace, undermine the interim agreement, and create obstacles—through acts of terror and other means—in order to force Israel to negotiate with them, as well, and thus secure their own territorial concessions.[15]

Aftermath

Egypt later violated the terms of the ceasefire agreement, though the violations were not substantial.[16]

These agreements laid the groundwork for the eventual Camp David Accords, where Israel agreed to withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula and the Straits of Tiran, ceding full security control to Egypt. The concessions and territorial withdrawals significantly weakened Israel's strategic position, particularly concerning access to the Red Sea, a vital maritime route for international trade and military operations.

Over time, the security limitations imposed by the Camp David Accords, which restricted both Egyptian and Israeli military presence in the Sinai Peninsula, undermined effective governance and enforcement in the region. While intended to serve as a buffer zone to protect Israel from potential threats, these restrictions instead created a security vacuum in the Sinai, allowing numerous terrorist groups to establish a foothold and launch attacks on nearby Israeli cities.[17]

References

- ↑ “The Hidden Calculation behind the Yom Kippur War.” Hudson Institute; “Milestones: 1969–1976: The 1973 Arab–Israeli War.” Office of the Historian; “Anwar Sadat and the Camp David Negotiations.” Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training; “Arab–Israeli wars.” Britannica; “Yom Kippur War.” Britannica.

- ↑ Israel-Egypt Disengagement Agreement – Text.

- ↑ Egypt–Israel Separation of Forces Agreement (Sinai I); Memorandum of Conversation – Washington, November 29, 1973; Israel–Egypt Disengagement Agreement (1974) – Map.

- ↑ Joel C. Christenson, Anthony R. Crain, and Richard A. Hunt, The Decline of Détente: Elliot Richardson, James Schlesinger, and Donald Rumsfeld, 1973-1977, Vol. VIII (2024), chap. 9.

- ↑ Address, 10 Shevat, 5735. Toras Menachem vol. 79 p. ??; Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 pp. 334-335; Video; Audio.

- ↑ The Rebbe’s Diplomat: Joseph Ciechanover’s Hidden Role in Israeli History; Mr. Yosef Ciechanover Meets the Rebbe, January 1975 – Video.

- ↑ “Failure of Kissinger's Mideast Mission Traced to Major Miscalculations.” New York Times, April 7, 1975; “Israel Under Pressure.” New York Times, July 10, 1975.

- ↑ Letter From President Ford to Israeli Prime Minister Rabin; Yitzhak Rabin, The Rabin Memoirs (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 256.

- ↑ Presidential Candidates Open to Leveraging American Support for Israel – Arab Center Washington DC; Shuttle Diplomacy and the Arab-Israeli Dispute, 1974–1975 – Office of the Historian; “US Delay Hinted on Arms to Israel.” New York Times, April 1, 1975; “Israelis in Tel Aviv Stone U.S. Embassy.” New York Times, April 1, 1975; Senate Letter Condemning President Ford on Blaming Israel for Peace Process Suspension (May 1975); Seventy-six US Senators Urge President Ford to Stand with Israel – Center for Israel Education.

- ↑ Interim Agreement between Israel and Egypt; Sinai Agreement – National Archives.

- ↑ Here's My Story – Ran Ronen-Pecker.

- ↑ “Israeli Defense Minister General Moshe Dayan on Face the Nation.” February 1972.

- ↑ Address, 19 Kislev, 5736. Toras Menachem vol. 82 p. ??; Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 pp. 248-249; Audio.

- ↑ Arab-Israeli Ceasefire of 1970 – cia.gov; “Dayan Urges U.S. to Compel Egypt to Respect Truce.” The New York Times, August 14, 1970; “Mideast Cease-Fire.” The New York Times, August 22, 1970.

- ↑ Address, 19 Kislev, 5736. Toras Menachem vol. 82 p. ??; Sichos Kodesh vol. 1, p. 250; Audio.

- ↑ “Arab Disunity Gives Israel A Respite on Its Frontiers.” The New York Times, August 30, 1976; “Israel Sees an Egyptian Drift Away from Camp David.” The New York Times, April 13, 1982.

- ↑ Ansar al Jihad in the Sinai Peninsula announces formation; Egypt’s Shifting Hamas Policies; “Egypt Army Operation Nets Militants in Sinai.” Reuters, August 16, 2011; Terrorism in the Sinai Peninsula: A Safe-Haven for Jihadists?; Israel's Sinai Dilemma – The Washington Institute.