Prelude to the Yom Kippur War 1967-1973

Setting the Ground (1967-1973)

War of Attrition (1969-1970)

Following Israel’s decisive victory in the Six-Day War of June 1967, hostilities between Israel and Egypt persisted. This prolonged conflict, known as the War of Attrition (1969–1970), was an attempt by Egypt to reclaim the Sinai Peninsula, conquered by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War, through extended military pressure. Egypt also sought to rebuild its military capabilities with substantial assistance from the Soviet Union.[1] Israeli shelling of Egyptian positions along the Suez Canal hindered the construction of new fortifications and the deployment of new surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems intended to protect the area from attacks by Israel’s air force.[2]

Ceasefire Agreement (1970)

Under significant pressure from the United States and the Soviet Union, on August 7, 1970, Israel and Egypt agreed to a ceasefire as an initial step toward future peace negotiations. The agreement prohibited any changes to the military status quo or the construction of new military installations within the designated ceasefire zone.[3]

During the negotiations leading up to the ceasefire and subsequent to its signing, the Rebbe warned both in private communications with Israeli government and military leaders, as well as in public addresses, that Egypt would use the ceasefire to strengthen its military presence along the Suez Canal. He further expressed the concern that once Egypt had fortified its positions and improved its military standing, it would have no incentive to make peace, thus leading to a new war.[4]

Over the following months, Egypt deployed advanced Soviet-made SAM-2 and SAM-3 anti-aircraft missile systems along the western bank of the Suez Canal, violating the terms of the agreement. This deployment formed the largest anti-aircraft network ever assembled in history, effectively establishing a defensive umbrella against Israel’s air force, extending 15 to 20 miles into the Sinai Peninsula.[5]

In an August 24, 1971 letter to General Aharon Yariv, Director of Israel’s Military Intelligence (AMAN), the Rebbe conveyed his grave concerns regarding the ramifications of the ceasefire and the resulting shift in the balance of power between Egypt and Israel:

- [Since the implementation of the ceasefire,] the balance of power has steadily shifted, and it has become increasingly clear that American materiel cannot match the volume or quality of Soviet aid . . .

- The claim has recently been made in military circles that the IDF is now much more powerful than it was during the Six-Day War. While this statement is true on its own, it entirely ignores the core issue:

The Rebbe also warned against Israel’s reliance on the Bar-Lev Line, a fortified defense system constructed along the Suez Canal during that period. He cautioned that static fortifications were vulnerable and ineffective in modern warfare and argued that depending on such a line would invite disaster.[6][7]

Israeli Concessions (1967-1973)

Following the 1967 victory, Israel repeatedly signaled its willingness to make territorial concessions, which were rebuffed by Egypt and Syria.[8] Seeking to prompt further Israeli concessions, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat initiated preparations for war. Aware that a full reconquest of the Sinai was unattainable, his objective was to secure only modest territorial gains through military action, intending to leverage these successes to shift the diplomatic balance and bring a weakened Israel to negotiations under more favorable terms for the Arab nations.[9]

The Rebbe later linked the resurgence of the conflict to discussions about territorial concessions following the Six-Day War, arguing that in the wake of Israel’s decisive victory, the Arab nations had been deterred and did not expect to regain their land. He maintained that the prospect of territorial concessions was perceived in the Arab world as a sign of Israeli weakness, which incentivized and emboldened its enemies to pursue further Israeli concessions through diplomatic pressure and renewed conflict.[10]

Spiritual Leadup — An Urgent Call

On June 5, 1973, the Rebbe issued an urgent call to ensure that every Jewish child received a proper Jewish education. Through public addresses and letters over the coming weeks and months, he repeatedly urged widespread involvement in making Jewish education accessible to as many children as possible, particularly during the summer months when schools are not in session.[11]

On June 20, the Lubavitch News Service issued a press release, the first of several conveying the Rebbe’s call to the public:

- LUBAVITCHER REBBE URGES SUMMER EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS FOR JEWISH YOUTH

- In his appeal the Rebbe also asked that existing overnight summer camps exert special effort to accommodate more children. [. . .]

- The Rebbe said that he would partially subsidize the costs of sending these children to such summer camps.

- Merkos L'Inyonei Chinuch, the educational arm of the Lubavitcher movement, announced that in accordance with the Rebbe's instructions it has directed its world-wide network of summer camps to undertake emergency expansion measures to accommodate additional campers.

In July, the Rebbe began associating this call to action with the spiritual power of children in countering potential threats:[12]

- The psalm states, “From the mouth of infants and babies, You have established strength to destroy the enemy and avenger.” [13]In order to go to war and prevail over an enemy, it would seem that trained soldiers are needed, who, according to the Torah, begin their service at the age of twenty.

- Yet, this verse teaches that the true way “to silence the enemy and avenger” is through “the mouths of babes and suckling's, You have established strength.” As our sages explain, “strength” refers to Torah—meaning that it is the prayer and Torah study of young children that holds the power to nullify and defeat the enemy.[14]

Toward the end of July and throughout August, the Rebbe further expanded on this theme, encouraging Jewish children to give charity regularly, pointing to it as another means of countering adversaries.

During this period, Israel was experiencing a sense of stability. The prevailing assessment was that Israel’s control over the territories captured in 1967 significantly strengthened its strategic position, enhanced its deterrence capabilities, and reduced the threat of war. Prime Minister Golda Meir echoed this sentiment regarding U.S. support for Israel in March 1973 during a meeting with U.S. President Richard Nixon, stating, “We [have] never had it so good.”[15]

The widespread belief in Israel’s strength and security shaped the ruling Labor Party’s campaign for the October 1973 elections. Campaign materials visually conveyed this message, including an image of an IDF soldier bathing in the Suez Canal alongside the slogan: “We have never had it so good.”[16]

In an address on September 15, twelve days before Rosh Hashanah, the Rebbe instructed that special rallies for children be organized in the days leading up to the new year, where the children would pray together and give charity.[17] The Rebbe specifically requested that one such rally be held at the Western Wall.[18] He emphasized the significance of holding these rallies during this period:

- By concluding the year in this manner, “From the mouths of infants and babies, You have established strength to destroy the enemy and avenger,” ensuring that all adversities and spiritual indictments will be completely neutralized.[19]

In the New Year - Upping the Ante

As the year 5734 began, the Rebbe continued to amplify his call with growing urgency. At a gathering held in honor of the anniversary of his mother’s passing six days into the new year, the Rebbe made special mention of the children, inviting them to lead the crowd in song.[20]

In an open letter addressed to Jews worldwide, the Rebbe addressed the enduring strength of the Jewish people. He emphasized that despite their small numbers relative to other nations, their true strength lies not in quantity but in quality. The Rebbe explained that by living in accordance with the teachings of the Torah, Jews connect to a divine power that transcends the physical realm, ensuring that spiritual quality will ultimately triumph over quantity:

- G‑d has given [the Chosen People] a special task as a nation among the nations of the world. In the words of the Prophet Isaiah: “Thus said the L‑rd G‑d, Creator of the heavens...the earth and its creatures...‘I’ll protect you and set you up as a covenant-people for a light of the nations.’” [. . .]

- So must also the Jewish people, as a nation, always be mindful of its special purpose and not underestimate its powers[. . .]

- There is a tendency sometimes to determine such endeavors on the basis of quantitative rather than qualitative criteria. Wherefore also in the area of these endeavors the Jewish people have been given the directive: “Not by might, nor by power, but by My spirit, says G‑d.” To the Jewish people and Jewish community (even to the Jew as an individual) special Divine capacities (“My spirit”) have been given to carry out their task in the fullest measure. For, where Jews are concerned, their physical powers are linked with, and subordinated to, spiritual powers, which are infinite.

- An historic example of this is found in the time of King Solomon, when the Jewish people stood out among the nations of the world by virtue of having attained the highest degree of its perfection [. . .] (notwithstanding the fact that even then Jews constituted numerically and physically “the fewest of all the nations”) [. . .]

- Consequently, also while in exile Jews must not ignore their task, nor underestimate their capacities, however limited their material powers may be, inasmuch as a Jew’s material resources, as already noted, are bound up with the spiritual, and in the spiritual realm there are no limitations also during the time of exile.[21]

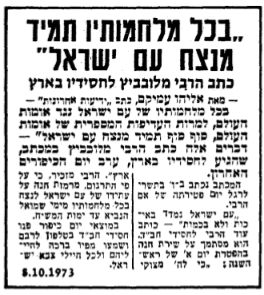

An article from Yediot Ahronot reporting on the Rebbe’s pre-war letter regarding Israel’s upcoming victory.

The following day, October 3, a children's rally was held at 770 in accordance with the Rebbe's instruction, during which he distributed coins for the children to give to charity.[22]

On October 5, Yom Kippur eve, the Rebbe appended a footnote[23] to his open letter, referencing biblical wars in Jewish history, highlighting how the Jewish people had always emerged victorious and how, with God's help, this would continue until the coming of Moshiach. The Rebbe instructed that the revised letter, including the additional footnote, be sent to the Chabad communities in Israel to be distributed before the onset of the holiday.[24]

The Attack

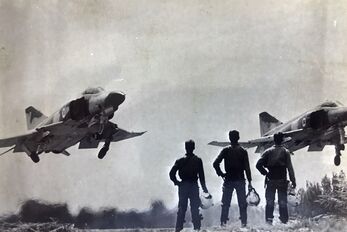

On October 6, at 2:00 PM Israel Time (7:00 AM Eastern Time), Egypt and Syria launched a simultaneous surprise attack against Israel, unprecedented in its scale and intensity, marking the beginning of the Yom Kippur War. Within two hours, Egyptian forces successfully crossed the Suez Canal, overrunning the Israeli fortifications at the Bar Lev Line on the Suez, and establishing a large beachhead on the Israeli side. Meanwhile, Syrian troops advanced into the Golan Heights. By evening, hundreds of Syrian tanks had pushed through the southern half of the Golan Heights, with no IDF forces remaining between the Syrian advance and the civilian population centers in the Galilee.

When the Rebbe arrived at 770 that morning, one of his secretaries informed him that war had broken out in Israel. The Rebbe simply responded, “I know.”[24] During Ne'ilah, the final and most solemn prayer of Yom Kippur, he was heard crying profusely, his head covered with his tallis.[25]

In a public address on October 9, three days after the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War, the Rebbe explained that his emphasis on strengthening Jewish education for children throughout the summer had served as a spiritual preparation for the war—albeit without consciously knowing the full import of his urgent campaign:

- There is a concept that “He prophesied but did not know what he was prophesying.”[26]—meaning that a person may take action without initially understanding its full purpose, only to later realize that it was, in fact, timely [and necessary].

- Throughout the summer, the theme of “From the mouths of infants and babies, You have established strength to silence the enemy and avenger” was a recurring focus…

- What prompted me to emphasize this? Over the years, I have spoken about it occasionally, but never with such intensity and urgency. Why now? Only now has it become clear that the need to “silence the enemy and avenger” had become especially pressing.[27]

Lead up to the war

In late 1972, Egypt began bolstering its military with Soviet-supplied fighter jets, Scud-B missiles, anti-aircraft missiles, tanks, and anti-tank weapons, while adopting Soviet tactics and replacing many generals.[28] Soviet military advisors provided significant assistance in Egypt’s preparations for war.[29]

In April 1973, Syrian President Hafez al-Assad agreed to join Egyptian President Anwar Sadat in launching a coordinated attack on Israel, with the goal of reclaiming the Golan Heights lost to Israel in the Six-Day War.[30]

Despite numerous warning signs, most in Israeli military and intelligence leadership dismissed Egyptian military buildup as an attempt by Sadat to strengthen his position in negotiations with Israel and the superpowers.[31]

In May[32] and August,[33] however, Egypt conducted military exercises along the Suez Canal, with Syria joining in May with drills in the Golan Heights. In response, Chief of Staff David Elazar twice ordered a partial mobilization of Israeli forces. When no attack followed, Elazar faced criticism over the financial cost of the mobilizations, approximately $10 million, respectively.[34]

On September 25, after meeting with Sadat and Assad in Alexandria, King Hussein of Jordan secretly traveled to Israel to deliver an in-person warning to Prime Minister Golda Meir about the imminent Egyptian-Syrian attack.[35] Israel’s leadership remained unconvinced of the threat, sending only limited reinforcements to the Golan Heights.[36]

Israel’s intelligence services deemed the chances of war unlikely, believing that despite Egypt’s designs on significant territorial gains in the Sinai, they still lacked the capability to counter Israel’s Air Force, or to strike targets accurately inside Israel. Analysts concluded that Egypt would not initiate hostilities without additional Soviet offensive weaponry, and that Syria would not attack without Egypt.[37] President Richard Nixon wrote in his memoirs, “as recently as the day before [the Egyptian-Syrian attack on Israel], the CIA had reported that the war in the Middle East was unlikely.”[38]

On October 1, Egypt initiated military exercises along the Suez Canal, paralleled by Syrian reserve call-ups and maneuvers in the Golan Heights. Having observed a total of 20 separate Egyptian mobilizations from January to September 1973, Israel’s Military Intelligence (AMAN) dismissed these actions as routine and non-threatening. The Egyptian exercises were seen as a repetition of the events in May, when Israel had mistakenly believed war was imminent.[39]

Pivotal Hours

In the days before the war, signs of an impending assault emerged, including the evacuation of Soviet advisers from Egypt and Syria, and, on the eve of the war, an unprecedented concentration of Egyptian forces and crossing equipment along the Suez Canal. Israel’s intelligence community began to issue sounds of concern.[36][40]

On October 5, Ashraf Marwan, an Egyptian spy embedded within President Anwar Sadat’s inner circle and the son-in-law of former President Gamal Abdel Nasser,[41] warned Mossad Chief Zvi Zamir that war would begin “towards evening” the next day. Despite Marwan’s earlier, incorrect, warning in April 1973, when he had predicted a war would commence in mid-May, this intelligence still carried significant weight.[36] Late on the night of October 5, Zamir relayed Marwan’s warning to Israeli officials, who estimated that the war would start at 6 p.m. on Yom Kippur, October 6. At this point, the Israeli military and intelligence leadership were convinced that war was imminent.[36][42]

Yom Kippur

At 8:05 a.m. on October 6, Yom Kippur morning, Prime Minister Golda Meir, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, Chief of Staff David Elazar, and other officials convened to assess the situation. Elazar proposed mobilizing 100,000 to 120,000 troops and launching a preemptive strike on Syrian airfields, missiles, and ground forces, arguing that it would cripple the Syrian Air Force, weaken their offensive capabilities, and prevent heavy Israeli casualties. Dayan, however, opposed a preemptive strike altogether, and favored a more limited mobilization of around 70,000 troops,[43] primarily due to U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger's warning that if Israel initiated an attack, it risked being perceived as the aggressor, potentially endangering American support.[34][44]

After hours of debate and argument, Meir approved Elazar’s proposal, authorizing the call-up of approximately 100,000 troops—at full strength, the IDF numbered 350,000. However, heeding Kissinger’s warning, she ruled out a preemptive attack.[45] She informed Kissinger that Israel would not strike first, and urged the U.S. to appeal to Egypt, Syria, and the Soviet Union to prevent war.[34]

Critique

The Rebbe was highly critical of the decision not to implement a full mobilization or launch a preemptive strike, viewing it as indicative of a broader pattern in Israel’s strategic mindset. He argued that an early call-up would have saved countless lives. Such measures, he maintained, would not have been seen as acts of aggression but rather as legitimate self-defense and therefore would not have endangered U.S. military support:

- The argument against launching a preemptive strike held no ground, because when the opposing side is prepared to attack, a strike against them is not “aggression” but rather a preemptive war—an act of self defense, fulfilling the principle of “If someone comes to kill you, rise early to kill them first.”[46]

- Their argument against mobilization, to avoid being seen as the “aggressors,” was even more unfounded, since mobilization is not an offensive action, to begin with.[47]

The Rebbe further contended that had Israel launched a preemptive strike, it would have eliminated the necessity for U.S. military aid altogether:

- If Israel had launched a preemptive strike even just a few hours earlier, when it became completely clear that the enemy was preparing to attack—there would have been no war by the ninth day [when U.S. airlifts began to arrive in Israel]![34][48] The war would have been won much sooner, similar to the swift victory in the Six-Day War, and perhaps even more quickly. The existing stockpiles would have sufficed, without any need for additional weapons. . .

In a 1978 address, the Rebbe pointed to this instance as an illustration of the tragic consequences that can arise when political considerations take precedence over military advice in matters of national security. Referring to the meeting in the Prime Minister’s office on Yom Kippur morning, he noted that, despite broad agreement among those present that a preemptive strike or full mobilization could have saved many lives, the recommendations of military experts were ultimately disregarded in favor of political factors.

- Several hours before the war began, intelligence confirmed that Egypt had fully mobilized its army, and was ready to attack. It had previously been questioned whether this information was accurate, but had been confirmed to be true still several hours before the attack had begun. In a government meeting, military officials presented an assessment that a full mobilization could repel the attack and reduce casualties, potentially even deterring Egypt from proceeding altogether. At the very least, there would be fewer casualties than when the Egyptian attack proceeded without a full mobilization.

- An opposing view was then presented. It argued that, while a full mobilization was admittedly necessary from a purely military and security standpoint . . . it would, [however], risk angering the United States, potentially jeopardizing future arms supplies and aid. Instead, it was proposed to inform the U.S. of Egypt’s plans while proceeding with only a partial mobilization, accepting that this would inevitably result in more casualties in order to maintain strong U.S.-Israel relations.

In her autobiography, Meir expressed regret about not calling up the reservists:

- Today I know what I should have done. I should have overcome my hesitations. I knew as well as anyone else that [sic] full-scale mobilization meant and how much money it would cost, and I also knew that only a few months before, in May, we had had an alert and the reserves had been called up; but nothing had happened. But I also understood that perhaps there had been no war in May exactly because the reserves had been called up.

- That Friday morning I should have listened to the warnings of my own heart and ordered a call up. For me, that fact cannot and never will be erased, and there can be no consolation in anything that anyone else has to say or in all of the commonsense rationalizations with which my colleagues have tried to comfort me . . . I shall live with that terrible knowledge for the rest of my life. I will never again be the person I was before the Yom Kippur War.[52]

Other mentions

List additional letters, Sichos, etc., from the Rebbe on this subject, with links

They knew days before. Spoken from room after heart attack.9 Kislev, 5738

Had there been a preemptive strike, there would have been no need for the US airlift. Would have been completed in less than six days. And the airlift only came on the eighth or ninth day! 9 Kislev, 5738

We wouldn’t have needed the airlift. Ninth day. 9 Kislev 5738

They knew days before 9 Kislev, 5738

They knew that the Egyptian were attacking on Yom Kippur should have called the troops they were scared of America. 13 Tishrei 5739

Further Reading

Here list other related books, articles, etc.

References

- ↑ War of Attrition – Britannica; “Egypt Will Fight, Nasser Shouts.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, November 24, 1967; “The War of Attrition 50 Years On.” The Times of Israel, March 2, 2019; The War of Attrition (1968-70); “Beachhead Established; Egypt and Israel Clash Near Suez.” The New York Times, July 2, 1967; Bill Norton, The Arab-Israeli War of Attrition, Volume 2 (England: Helion and Company, 2023), 13.

- ↑ Arab-Israeli Ceasefire of 1970 – cia.gov; “Dayan Urges U.S. to Compel Egypt to Respect Truce.” The New York Times, August 14, 1970; “Mideast Cease-Fire.” The New York Times, August 22, 1970. Address, 28 Tammuz, 5730. Toras Menachem vol. 61 pp. 109-110; Sichos Kodesh vol. 2 p. 432.

- ↑ Israel-Egypt Ceasefire Agreement (1970) – Text; “Tough Road After Cease-Fire.” The New York Times, August 9, 1970.

- ↑ Letter, 1 Av, 5730. Igrot Kodesh vol. 26 p. 441. See also address, 20 Av, 5730. Toras Menachem vol. 61 p. 159; Sichos Kodesh vol. 2 pp. 460b-460c; “הרבי מלובאוויטש: הפסקת האש טעות חמורה” [in Hebrew]. Yonah Cohen, Hatzofeh, September 3, 1970.

- ↑ Arab-Israeli Ceasefire of 1970 – cia.gov; “Buildup On The Suez.” Time, September 14, 1970; SA-2 Surface-to-Air Missile — National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Letter, 3 Elul, 5731. Igrot Kodesh vol. 27 p. 205.

- ↑ Ariel Sharon and the Rebbe; Letter, 18 Av, 5730. Igrot Kodesh vol. 26 p. 451; English Translation.

- ↑ Israeli Government-Designed Peace Plan After June 1967 War, Center for Israel Education; Israeli Government Resolution on Withdrawal for Peace, June 19, 1967 (Text); “Three No's Resolution,” 4th Arab League Summit in Khartoum, September 1, 1967 (Text); Abba Solomon Eban, פרקי חיים, vol. 2 [in Hebrew] (Israel: Sifriyat Ma’ariv, 1978), 430; “The Astonishing Israeli Concession of 1967,” The Atlantic, June 7, 2017.

- ↑ The Hidden Calculation Behind the Yom Kippur War, Michael Doran, Hudson Institute (October 2, 2023); Yom Kippur War – Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ Address, 13 Tishrei, 5734. Toras Menachem vol. 74 pp. 79-80; Likkutei Sichos vol. 14 pp. 405-406; Audio; Address 18 Adar, 5739. Sichos Kodesh vol. 2 p. 322; Audio; Address, 24 Kislev, 5746. Toras Menachem vol. 1 p. 618; See address 14 Adar, 5738. Sichos Kodesh vol. 2 p. 39; Audio; Address 22 Sivan, 5742. Toras Menachem vol. 3 pp. 1663-1664; Sichos Kodesh vol. 3 pp. 19-20; Video; Audio.

- ↑ Address, 5 Sivan, 5733. Toras Menachem vol. 72 pp. 276-279; Letter, 12 Sivan, 5733. Igros Kodesh vol. 28 pp. 233-236; Letter, 12 Sivan, 5733. Igros Kodesh vol. 28 pp. 236-237; Letter, 17 Sivan, 5733. Igros Kodesh vol. 28 pp. 238-240.

- ↑ Letter, 15 Tammuz 5733. Igros Kodesh vol. 28 pp. 253-255; Letter, 15 Tammuz, 5733. Igros Kodesh vol. 28 pp. 258-260; Address, 28 Tammuz, 5733. Toras Menachem vol. 73 pp. 101-102; Letter, 27 Tammuz, 5733. Igros Kodesh vol. 28 pp. 274-275; Letter, Days of Elul, 5733. Igros Kodesh vol. 28 pp. 306-307.

- ↑ Psalms 8:3.

- ↑ Address, 12 Tammuz, 5733. Toras Menachem vol. 73 pp. 27-28; Sichos Kodesh vol. 2 pp. 249-250; Video; Audio.

- ↑ Memorandum of Conversation — March 1, 1973.

- ↑ "מלחמת יום הכיפורים בעיני מזכיר המדינה האמריקאי הנרי קיסינג׳ר" [in Hebrew], Zakai Shalom, Institute for National Security Studies – Tel Aviv University, Vol. 26, Issue 1, March 2023; "איך המערך ניצח שוב בבחירות?" [in Hebrew], Tal Shalev, The Post, October 1, 2013.

- ↑ Letter, 19 Elul, 5733. Igros Kodesh vol. 28 pp. 325.

- ↑ Our Spiritual Weapons,

- ↑ Address, 18 Elul, 5733. Toras Menachem vol. 73 p. 206; Likkutei Sichos vol. 14 p. 263.

- ↑ Our Spiritual Weapons, Living Torah Program 994.

- ↑ Letter, 6 Tishrei, 5734. Likkutei Sichos vol. 9 pp. 484-487. English Letter.

- ↑ Diary, Aharon Dov Halperin; Diary, Aharon Yitzchok Leichter; Diary, Ezra Mafai.

- ↑ Footnote 10.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Stop the Enemy! The Spiritual Battle of the Yom Kippur War,” A Chassidisher Derher 98 (175) (Tishrei 5781), 55.

- ↑ “Yom Kippur with the Rebbe,” A Chassidisher Derher 73 (150) (Tishrei 5779), 47; Shalom Yerushalmi, Yossi Elitov, and Aryeh Ehrlich, Berega Ha’emet [in Hebrew] (Modi’in, Israel: Dvir, 2017), 140–142.

- ↑ Genesis 45:18, Rashi.

- ↑ Address, 13 Tishrei, 5734. Toras Menachem vol. 74 p. 78; Likkutei Sichos vol. 14 p. 404; Audio.

- ↑ Mohamed Heikal, The Road to Ramadan (London: Collins, 1975), 22; “Perception, Misperception and Surprise in the Yom Kippur War: A Look at the New Evidence,” Abraham Ben-Zvi, Journal of Conflict Studies 15, no. 2 (Fall 1995), 10.

- ↑ The Soviet-Israeli War, 1967-1973: The USSR's Military Intervention in the Egyptian-Israeli Conflict, Isabella Ginor and Gideon Remez (Oxford Academic, online ed., June 20, 2019), 281–292.

- ↑ “The Battle for the Golan Heights in the Yom Kippur War of 1973: A Battle Analysis,” Benjamin Stanley Scott, Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects (2006), 3; “Anwar el Sadat and the Art of the Possible: A Look at the Yom Kippur War,” Cosmas R. Spofford and Warren L. Henderson, National War College (2001), 7; Arab-Israeli War 1973 — U.S. Department of State Archive.

- ↑ “The Yom Kippur War: A Case of Deception and Misperception,” Talia Segal, Julie Ahn, and Annie Jalota, CIA Project, 1973 War Project, 10.

- ↑ Chaim Herzog, The War of Atonement: The Inside Story of the Yom Kippur War (Israel: Steimatzky's Agency, 1975), 29; “The 1973 Arab-Israeli War: Arab Policies, Strategies, and Campaigns’” Major Michael C. Jordan, United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps University Command and Staff College (1997).

- ↑ Saad el-Shazly, The Crossing of the Suez, Revised Edition (American Mideast Research, 2003), 209–210; “1973 Arab-Israeli War; Code name: Operation Badr,” Mohamed Zain, Egypt Today, October 7, 2017; “Yom Kippur: Deception in Warfare,” MSG O’Neal, United States Army Sergeants Major Academy (December 7, 2007), 4.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 “Kissinger's triumph began in trauma.” The New York Times, June 23, 1974.

- ↑ Abraham Rabinovich, The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter That Transformed the Middle East (New York: Schocken Books, 2004), 50.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 “Enigma: The Anatomy of Israel’s Intelligence Failure Almost 45 Years Ago,” Bruce Riedel, Brookings, September 25, 2017.

- ↑ “The Yom Kippur Intelligence Failure After Fifty Years: What Lessons Can Be Learned?” I. Shapira, Intelligence and National Security (Informa UK Limited, Taylor & Francis Group, 2023); “Intelligence During Yom Kippur War (1973),” Jewish Virtual Library

- ↑ Richard Milhous Nixon, The Memoirs of Richard Nixon (United States: Easton Press, 1988), 920; “President Nixon and the Role of Intelligence in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War,” Harold P. Ford, Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, (2013), 17.

- ↑ “The October 1973 War in the Sinai,” Arden B. Dahl, Command Dysfunction: Minding the Cognitive War (Air University Press, 1998), 66.

- ↑ “Egypt's Sadat is 'not worth tomatoes,' reservist professor assured Israel's military intelligence before 1973 war,” Mitch Ginsburg, The Times of Israel, October 24, 2012;

- ↑ “Egyptian 'Spy for Israel' Found Dead Outside London Flat,” The Guardian, June 28, 2007.

- ↑ “The Intelligence Failure of the Yom Kippur War of 1973” Stephen Spinder, Armstrong Undergraduate Journal of History (April 22, 2016); The Hidden Calculation Behind the Yom Kippur War, Michael Doran, Hudson Institute (October 2, 2023); “Mossad Reveals New Details About Key Egyptian Spy Who Warned Israel That Yom Kippur War Was Imminent,” Ofer Aderet, Haaretz, September 7, 2023.

- ↑ The Story of the Yom Kippur War, October 1973 — Israel State Archives.

- ↑ Abraham Rabinovich, The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter That Transformed the Middle East (New York: Schocken Books. 2004), 89; Memorandum of Conversation between Dinitz and Kissinger, 7 October 1973, pp. 4-5.

- ↑ “Worse than the worst-case scenario: The dreadful hours before the Yom Kippur War,” Abraham Rabinovich, The Times of Israel, September 15, 2021.

- ↑ Brachos, 62b.

- ↑ Address, 9 Kislev, 5738. Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 p. 227; Audio.

- ↑ Operation Nickel Grass — Air Mobility Command Museum; “Operation Nickel Grass: The Airlift Race," Walt Napier III, 505th Command and Control Wing News (November 14, 2021); The 1973 Arab-Israeli War — Office of the Historian.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Sanhedrin 37a.

- ↑ Address, 9 Kislev, 5738. Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 p. 228; Audio.

- ↑ 13 Tishrei, 5739. Sichos Kodesh vol. 1 pp. 97-99; Audio.

- ↑ Golda Meir, My Life (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1973), 424-425.