The Instability of Monarchies

Overview

Israel's security requires engagement with neighboring regimes. However, inherent risks exist. Notably, the instability and unpredictability of these governments lead to the potential for swift, violent regime changes. Israel must resist the urge to create dependencies on these governments for long-term security, nor should it support the provision of advanced weaponry. Israel must place a strong emphasis on mitigating the dangers posed by the volatile nature of authoritarian governance.

Instability of Monarchies and Autocracies

Danger of Revolution

In a landmark talk during the winter of 1979, the Rebbe underscored the historical fragility of monarchies, especially those built on concentrated wealth and power, held by a small elite. Pointing to the recent overthrow of the Shah of Iran as an example, he explained that the revolution was not an aberration but part of a broader historical pattern, recalling a similar uprising of the masses that he witnessed in his youth:

- When the 1917 Russian Revolution occurred, people were incredulous, "How could this be? The Czars have ruled for 300 years, and suddenly, along come a handful of peasants with a handful of soldiers, who believe they can overthrow the Czar—it will never happen!"

- And when the revolution actually occurred, the surrounding governments chose to believe that such “uncivilized behavior” was unique to Russia, and would remain contained to its borders. In reality, however, the 1917 Russian Revolution spread to all the surrounding countries.[1]

The Rebbe drew a direct connection between the conditions that led to these revolutions, and the potential for swift regime change in Middle Eastern monarchies and autocracies. He identified inequality and exploitation of the proceeds of natural resources as triggers for societal collapse—a pattern not confined to a specific era, with the potential to recur at any time.

When wealth and power are concentrated in the hands of a small group of autocratic leaders, combined with systemic inequality, a perfect breeding ground for revolution is created. What happened in Russia, and more recently in Iran, must serve as warnings: Monarchies, however stable they may seem, can fall quickly, even while propped up by Western arms and support.

Skeptical about the durability of the Saudi Arabian monarchy, the Rebbe pointed to the fact that “three individuals—one family—amass tens of billions of dollars annually,” while their subjects become increasingly aware of this inequality. Such a system, reliant on such extreme imbalance, could hardly be considered stable:

- The entire monarchy is propped up through using a portion of its wealth to hire soldiers for protection. They pay exorbitant sums to bodyguards and the military who protect this family, ensuring that this income of tens of billions of dollars every year continues to flow into their pockets.[1]

Because the vast wealth was spent on interests that did not benefit the citizens, the government was perceived as disconnected from their needs. Based on historical precedent, the Rebbe argued that, inevitably, a situation would arise where the loyalty of the military would be uncertain. In such circumstances, the “hired help,” the army and bodyguards, would easily see their allegiance swayed by different values or higher pay. This vulnerability could be articulated to the populace with a simple argument:

- “Listen here! You are millions, while those in power are just three, four, ten, maybe fifteen people. The people guarding them are no more than hired guns.

- If the military is offered double, triple, or quadruple their present pay, why would they continue protecting thirteen people against thirteen million? It wouldn’t be worthwhile.”[2]

Arming Fragile Regimes

The Rebbe pointed to the approach embraced by the United States, that selling or giving advanced arms to these regimes would help assure their stability. Such actions could backfire, resulting in the weapons falling into the hands of extreme elements, only to be used against those who supplied them, or their regional proxy, Israel.[3]

In a similar vein, providing advanced weaponry and resources would not ensure the country’s safety or stability, if the loyalty of its citizens was not guaranteed:

- Some are under the impression that sending planes [to Saudi Arabia] will serve to protect the country.

- But an airplane cannot defend anything on its own. Inside that plane, there must be a person who cares for what he is defending. This person must be an expert in operating the aircraft, and must be willing to take orders from someone who pays him.

- The pilots that are being hired there are completely apathetic. As long as they are being paid, they’ll do the job. But will they risk their lives for that cause? So far, that reality has not existed.[4]

Ramifications for Strategic Agreements

The Rebbe viewed these historical regime collapses as important reminders that alliances with monarchies—often perceived as stable for decades, or centuries—could be upended swiftly, due to internal or external pressures.

As such, he cautioned against relying on guarantees made by such governments for Israel's vital security needs. Israel’s well-being, whether in economic or security matters, must be built on durable, long-lasting foundations, rather than on commitments by fragile partners.

In the aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis—when the Arab oil states, led by Saudi Arabia, embargoed Israel—the Rebbe argued that even a Saudi Arabian guarantee to lift the embargo would carry little weight:

- Even if Saudi Arabia were to promise [to provide Israel with oil], no one knows how long it would last. No one even knows how long the king there will retain his power.[1]

Applied to Governmental Structures

Political Autocracies – Egypt

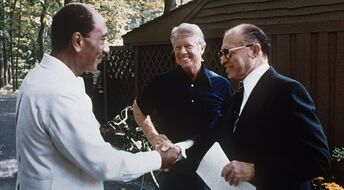

On September 17, 1978, Israel and Egypt signed the Camp David Accords, which laid the groundwork for a peace treaty in which Israel would return the Sinai Desert, along with its natural assets, including oil wells and underground deposits of source materials for nuclear development, to Egypt. In exchange, Egypt would establish diplomatic relations with Israel and reopen the Suez Canal to Israeli shipping.[5]

The Rebbe strongly opposed this treaty. One reason was his view that the stability of a government such as Egypt’s would always remain in question. He deemed exchanging tangible “hard” security assets, which are necessary for Israel’s security, for a piece of paper promising peace, signed by a government that was in danger of overthrow at any moment, as beyond dangerous.

In a talk delivered three days after the signing of the accords, the Rebbe referred to President Sadat, who had been willing to break deep-seated taboos in Egyptian society by engaging with Israel, despite the opposition of large segments of Egypt's more radical society.

The Rebbe warned that neither the president’s own hold on power, nor the consistency of his attitude, could be relied upon to last forever:

- Israel’s only supposed gain is a verbal promise from someone whose own position is uncertain—who knows how long he’ll remain in power? And even while he remains, he is dependent on a wealthy ‘uncle’ sitting somewhere in the Arabian Peninsula for support—namely, Saudi Arabia.

- This individual has promised that, if everything proceeds in a manner he desires, he will agree to engage in discussions regarding a peace agreement with Israel. Subsequently, over the course of years, there will be a process leading to normalization of relations, diplomatic ties, etc…

- It is unknown how long he will remain in power and, while he does, whether he will act independently, or whether he will follow the whims of those funding him, to whom he feels indebted.[6]

Three years later, President Sadat was assassinated by Egyptian Islamic extremists, at least in part as a result of his peace treaty with Israel.[7]

Authoritarian Regimes – Saudi Arabia and the “Oil Emirates”

During the Second Yemenite War of 1979, the United States supplied Saudi Arabia with an array of arms, including fighter jets and a Carrier Strike Group, allowing the regime to protect itself from a potential incursion by neighboring Marxist South Yemen.[8] In the 1979 address, after detailing the volatile state of Saudi Arabia and the similar nature of its surrounding emirates—“mini kingdoms” in the Rebbe’s vernacular—the Rebbe emphasized that the strategy of arming fragile regimes had already been attempted in Iran, and had failed. Most of the weaponry supplied by the United States ended up in the hands of the new, highly radical, Khomeini regime.

The Rebbe lamented that the clear lessons from this outcome were being ignored:

- You’d think [the United States] would take note of the instability and would act accordingly. However, just as no precautions were taken with Iran prior to its revolution, none are being taken with Saudi Arabia. What are they doing? Sending arms!

Despite the United States’ intention to stabilize the region, its actions had the opposite effect, exacerbating an already precarious situation. By providing Saudi Arabia with advanced weaponry, the Rebbe argued, the US had heightened the stakes for hostile actors—both neighboring nations and internal factions—making the kingdom a more attractive target. If these groups had previously been drawn to Saudi Arabia’s economy and vast oil reserves, they now had an additional incentive: a cache of advanced American arms waiting to be seized.

Other Mentions

- List additional letters, Sichos, etc., from the Rebbe on this subject, with links.

Further Reading

- Here we will list other related books, articles, etc.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Address, 19 Adar, 5739. Sichos Kodesh vol. 2, p. 328; Video, Audio.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Address, 19 Adar, 5739. Sichos Kodesh vol. 2, p. 329; Video; Audio.

- ↑ “Oil Affects Israeli Stance.” Washington Post, February 23, 1979.

- ↑ Address, 19 Adar, 5739. Sichos Kodesh vol. 2, p. 334; Video, Audio.

- ↑ Camp David Accords – Britannica.

- ↑ Address, 18 Elul, 5738. Sichos Kodesh vol. 3, pp. 422-423; Audio.

- ↑ "Sadat Assassinated." The New York Times, Oct. 7, 1981; “The assassination of Egypt's President Sadat.” BBC News, October 7, 2015.

- ↑ “U.S. Sends Ships To Arabian Sea In Yemen Crisis.” The New York Times, March 6, 1979.