The 329 Paradigm

Overview and Basics

Overview

Presenting directives for how to handle threats to life on Shabbat, the Code of Jewish Law rules: If non-Jews besiege a city on Shabbat and lives are at stake, Jews must take up arms on Shabbat in order to defend themselves. However, the law declares a critical distinction, when one must take up arms even if there is no threat to life, and even if the enemy is not laying siege: "If the city is near the border," it must be defended "even if they come only to plunder straw or hay."

Due to its strategic importance, any potential threat in a border town must be treated as a life-threatening situation, as its loss would endanger the entire area beyond. A Jew is to risk his own life to confront the raiders, even if they know that the adversary's intent at present is merely to plunder straw or hay, and it expressly does not desire to do battle.

The Rebbe pointed to this law as a guiding Torah principle, providing a framework to identify and evaluate security threats and to chart appropriate responses.

The potential for an enemy gaining a strategic advantage must be treated as an immediate threat to life, even if, at present, the situation presents as innocuous. Allowing such strategic advantage to the enemy is forbidden, as it will necessarily result in loss of life, G-d forbid.

Provenance

The earliest source for this law is recorded in the Book of Samuel, and is explained in the Talmud. During the times of King Saul, King David received word that a raiding party of Philistines was pilfering grain from the city of Ke’ilah. Despite the fact that it was Shabbat, David was told to attack:

- And they told David, “Behold, the Philistines are waging war against Ke’ilah, and they are pillaging the threshing-floors.” And David inquired of the Lord, saying, “Shall I go and smite these Philistines?” And the Lord said to David, “Go, and you shall smite the Philistines, and save Ke’ilah.”[1]

The Talmud explains that although the attackers were merely engaged in theft—a monetary concern, with no threat to life—David violated Shabbat and fought them, because Ke’ilah was a border town.

- It was taught in a baraita: Ke’ilah was a town located near the border, and the Philistines only came on matters of hay and straw, as it is written: "And they are pillaging the threshing-floors." And the next verse states: "And David inquired of the Lord, ''Shall I go and smite these Philistines?" And the Lord said to David: "Go, and you shall smite the Philistines, and save Ke’ilah."[2]

The commentators explain that with this passage, the Talmud, and ultimately Jewish law, establishes specific guidelines to counter a threat to a strategic position. When a border town is at risk, extra precautions must be taken to avoid vulnerability. Because if an adversary gains access to city near the border, the risk exists that they might eventually return, conquer it, and it may serve as an opening to conquer the entire land.[3] In the words of Rashi:

- Lest the enemy capture the border city, and from there it will be easy for them to conquer the rest of the land.[4]

The Talmud’s statement is codified in all major works of Jewish law, turning the Talmud’s statement into a practical, and literal, ruling of Halachah. Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah,[5] Rabbi Yaakov ben Asher’s Arba’ah Turim, and Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi’s Code of Jewish Law,[6] all enumerate this law. Rabbi Yosef Karo’s classic Code of Jewish Law, Laws of Shabbat Chapter 329:6 codifies:

- If non-Jews besiege Jewish cities: If their goal is monetary, we do not desecrate the Shabbat [to protect ourselves]. But if they came to kill, or with no presented reason, we go out with weapons and desecrate the Shabbat [and battle them]. [However,] in a city near the border, even if they come only to plunder straw or hay, one must take up arms against them, even if it entails desecrating the Shabbat.

Rabbi Moshe Isserles in his glosses adds an additional clause:

- [The directive to take up arms applies] even if they haven’t yet come, but they merely intend to come.

Present-Day Application

Practical Relevance

In the Rebbe’s reading, this law is a guiding principle for Jewish communities, no matter their location: Any location, position, or asset of strategic defensive value that can serve to threaten security, must be treated as a matter of life and death. Relinquishing the asset will result in loss of life, God forbid.[7]

Beginning in 1977,[8] this ruling served as a touchstone of the Rebbe’s guidance on Israel’s security. On dozens of occasions, the Rebbe pointed to it as a practical tool to determine the proper course of action in the face of threats, and as a guide to strategic decisions.

Arguing against those who asserted that giving away land in exchange for promises of peace, the Rebbe declared:

- When non-Jews approach and demand “straw and hay” from Jews that live in a specific area—even outside of Israel—Torah provides clear guidance for what to do.

- The test, the ultimate criterion, is found in the Code of Jewish Law [. . .] If there is a concern that “the land may open up before them,” one must take up arms, even on Shabbat, and even if the threat is not yet fully realized.

- There are those who argue that this law only applies to a case of “non-Jews besieging,” where they approach with an army, lay siege, and declare that they have come for war—a war that is merely to take straw and hay. Whereas [Israel is] sitting [with the adversary] at a round table, with third-party mediators who pledge to assist both sides equally.

- However, this does not change the ruling. The sages emphasize that the reason for taking up arms is not to avoid war, nor to maintain peace among nations, but to prevent the possibility that “the land may open up before them.[9]

On another occasion, the Rebbe emphasized the law’s application even when the possibility of danger to life seems remote:

- This applies even if they have not yet arrived, but are merely indicating that they might possibly come. Even in cases of uncertainty—or multiple layers of uncertainty—Torah makes no distinction: One must take up arms and stand firmly against their entry. How much more so, it is forbidden to offer non-Jews any control over the land, Heaven forbid, or to grant them even a foothold in a place where Jews reside—even if it is home to only one solitary Jew.[10]

Even if, at present, no attempt by an enemy to cause death or injury can be discerned, a given location’s strategic importance requires any incursion, or even a potential incursion, to be treated as a direct risk to life today.

On numerous occasions, the Rebbe pointed to the obvious: Israel’s adversaries are not coming for straw and hay. They declare openly that they wish to attack and own the land itself.[11]

Immediacy of Threat

A key aspect of this ruling is the classification it applies to a seemingly minor strategic threat. The law es that relinquishing a tangible strategic asset will result in loss of life and must be prevented—to the extent of risking one’s life—even on Shabbat. Action is required immediately when the asset becomes threatened, even if the threat appears innocuous at the moment, as emphasized by the Rebbe in a 1980 letter to Rabbi Pinchos Meir Kalms:

- Because of the possible danger, not only to the Jews of this town but also to other cities, the Code of Jewish Law rules that upon receiving news of the gentiles (even only) preparing, Jews must mobilize immediately and take up arms even on Shabbos—in accordance with the rule that threat to life supersedes Shabbos.[12]

According to Torah, the guiding principle in every security decision must be whether it grants the potential adversary a position of strategic value. In short: Will physical protection be enhanced or, conversely, placed at greater risk?

Where 329 Applies

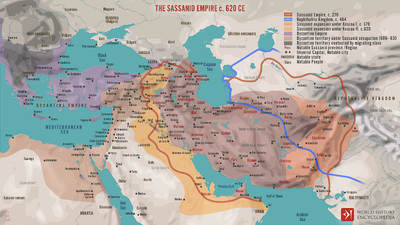

The requirement to protect a border city is not specific to Israel. In fact, the Talmud speaks in the context of the Jewish city of Naharda’a in the Roman Empire, which was on the border of the Sasanian Persian Empire.

- The 329 ruling refers to a case of non-Jews who approach a location where Jews reside — whether in the Holy Land or the diaspora, during the Temple era or the times of exile. Even if they claim they are coming only for benign purposes such as “straw and hay,” and this might be their genuine intention, nevertheless, the possibility remains that their entry, especially in a border city, may compromise the land's security.[10]

In his 1980 letter to Rabbi Kalms, the Rebbe writes:

- I have repeatedly emphasized that this Halachic ruling has nothing to do with the sanctity of Israel, or with "days of Mashiach," the future redemption, and similar considerations, but solely with the rule of preserving human life. This is further emphasized by the fact that this ruling has its source in the Talmud (Eruvin 45a), where the Talmud cites as an illustration of a "border-town" the city of Neharde’a in Babylon under the terms of this ruling (present-day Iraq)—clearly not in Israel. I have emphasized time and time again that it is a question of, and should be judged purely on the basis of, risk to life, not geography.[12]

In the Rebbe’s view, the entirety of Israel qualifies as a “border town,” both because of its small borders and because of the strategic nature of any territory in defense of the entire land.[8]

Definition of Strategic Position

Halacha is clear that any location that might “open up the rest of the land” must be protected at all costs, because it places Jewish life in jeopardy. But, what determines which positions threaten Jewish life?

The law in Section 329 determines threat to life solely by tangible security concerns (ignoring other factors like long-term economic health, or even supply of armaments, pressure from allies, etc.), so the only relevant metric for assessing threats must be practical security standards.

In addition to actual territories, the Rebbe applied the law to strategic assets, as well:

- Returning strategic territories or relinquishing oil reserves is directly linked to an immediate pikuach nefesh (life-threatening situation). These actions endanger the security of the Jewish people living in the Holy Land right away—not in months or years, but immediately!

- As has been discussed many times, oil is essential for powering tanks, planes, and other critical equipment. Handing over oil wells, which forces reliance on foreign sources to purchase oil, creates an immediate shortage—not months down the line, but the very next day! It is self-evident that maintaining a stockpile of oil sufficient for months is not feasible. The only way to ensure a steady supply is by retaining control over the oil wells and being able to extract oil directly from the source.[13]

Diplomatic gains and geopolitical considerations cannot factor into security decisions, as their focus is not on safeguarding life in the present. They focus on promises for the future or, in many cases, achieving an external objective. Politicians and diplomats who may seek benefits beyond safety should not be making decisions that pertain to the state of national security.[14]

Security Considerations

As normative Judaism does, the Rebbe looks at Halacha as a G-dly document. But the law must be applied in physical parameters. Halacha relies on a medical professional to assess physical risk; it similarly requires an objective standard and a qualified authority for security matters. Therefore, only a trusted military expert can be depended upon to make judgments about security threats and risks. Only they are trusted to determine whether any particular decision will protect or endanger Jewish life.[15]

Even military experts who lack up-to-date data or who factor in other non-military considerations cannot be entrusted with the responsibility of making security decisions. Once again, the sole concern in these matters is the safety of lives, and this must be evaluated with objectivity and precise expertise.[16]

In a 1981 letter to Rabbi Jacobowitz, the Rebbe pointed out that even the major decision makers in Israel admitted that relinquishing territory was not justified from a military perspective:

On another occasion, the Rebbe expressed his regret that military experts were mixing political considerations into their military decision-making:

- Even when asking a military expert—This is a source of deep pain: I asked one of my fellow Jews, and he didn’t know how to respond. He consulted with a military officer who said that it’s necessary to give away not just a small area, but a significant piece of land.

- I asked: “Did he explain the rationale?” They went back to the military officer and inquired about the reasons behind his statement that land must be surrendered—whether it would save lives or for other considerations.

- He replied: “No! The danger lies in surrendering the land. However, the hope is that by doing so, within three weeks, a month, or a year, we might achieve a true peace. For the sake of potential peace in three months, I am willing to risk the immediate lives of many Jews.”

- This is not a military discussion but a calculation based on reasoning. In this case, such reasoning contradicts the principles of the Shulchan Aruch.[18]

Territory

Not unlike Israel's original defense strategies, which treated strategic land buffers as central and vital,[19] the entire premise of 329 belies the fact that territory is not a, but the, foremost strategic asset. Raiders seeking hay and straw are viewed as mortal threats because, as the commentators explain, if an adversary gains access to city near the border, the risk exists that they might eventually return, conquer it, and it may serve as an opening to conquer the entire land.[3]

The settlement project serves an important role in the context of Israel’s security per Section 329.

Halacha makes it clear that the strategic positioning of cities is essential to protect the entire country from surrounding threats. If the positions between our enemies and us are not adequately secured, the entire land "is opened up before them." Therefore, it assigns utmost importance to the protection of these positions.

As expressed in the Rebbe's letter to Rabbi Jacobowitz:

- I am completely and unequivocally opposed to the surrender of any of the liberated areas currently under negotiation, such as Yehuda and Shomron, the Golan, etc., for the simple reason, and only reason, that surrendering any part of them would contravene a clear ruling in Code of Jewish Law (Orach Chayim, sec. 329, par. 6,7).[12]

For this reason, border settlements must be established around the entire country, effectively sealing off any gaps that could allow enemies to breach our security. These communities would ensure the protection of Jewish life in the entire country.

It is important to clarify that the purpose of these border settlements is not connected to the sanctity of the Holy Land or to the notion of further establishing Jewish settlement throughout Israel. The focus is solely on security and ensuring that the country's borders are fortified to protect against the enemy threats surrounding Israel.

Since the goal of these communities is to protect the borders and its inhabitants, the term “settlements” does not accurately reflect the true purpose of this mission, possibly leaving one with the impression that their purpose if religiously-driven settlement of the Holy Land. However, the intention is purely defensive: to protect the borders and the people within the land, and their name should reflect that.

- It must be explicitly emphasized that this is not about “settlements,” nor is it about “villages,” nor “towns” or “centers,” etc. Rather, it refers specifically to what is stated in Code of Jewish Law: “that the land should not be open before them.”[20]

The creation of settlements throughout Israel’s strategic territories also serves as a bulwark against the pressure facing the Israeli government; if an Israeli leader will find himself under impossible pressure to relinquish that territory, he will also find himself under terrible pressure to retain that territory, because of the presence of settlements.

Territories & Assets Gained in War

The key result of Section 329 is the rejection of the common model of “land-for-peace,” which argues that peace can be achieved by returning land to a hostile power or by establishing an Autonomy or Palestinian state within lands under Israel’s control. Section 329 sets forth an opposite approach—that peace can only be achieved by retaining land, and relinquishing land would only serve to exacerbate conflict.[21]

Torah teaches that when facing potential threats to Jewish safety, no risk is tolerable, and all measures must be taken to eliminate such dangers. This principle directly informs policy on land concessions:

Halacha emphasizes that maintaining control over strategic territory is the most secure way to protect its inhabitants. Conversely, relinquishing strategic positions “opens up the land” to the enemy, a situation Halacha strictly prohibits. Consequently, from a Halachic standpoint, conceding land is forbidden since it endangers the lives of its inhabitants.

Even when a peace agreement is offered in exchange for land, it should not be considered. A promise of security is theoretical—a mere “piece of paper”—and does not provide tangible or objective safety. Torah instructs us to prioritize military and strategic security that genuinely guarantees protection. Accordingly, we must never place ourselves in a vulnerable position by relinquishing control over any strategic area.

Hostility of the Enemy

The formulation of this law specifically states that it applies to all potential threats, not active enemies. “The term is ‘gentiles,’ not ‘enemies,’”[12] the Rebbe wrote.

- How much more so with enemies: Based on Israel’s modern history, Israel’s neighbors are hostile to its presence, despite their claims to the contrary. When evaluating their actions, their true intentions come to light. This implies that arms must be taken up to prevent any encroachment on Jewish territory, whether or not the said territory qualifies as a “border town.”

Application in Specific Events

Sinai War - Suez Canal Crisis

In 1956, Egypt nationalized the Suez Canal and had already begun blocking the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping the previous year. In response, Israel, in coordination with the United Kingdom and France, launched a military operation, successfully seizing control of the Sinai Peninsula. However, under significant pressure from the United States, Israel withdrew from the Sinai. This withdrawal bolstered Egypt’s standing as a leader in the Arab world, enabling it to regroup and eventually plan future attacks against Israel from this strategically vital region.

Post Six Day War

In the period following the Six Day War, the Arabs and the international community were awestruck by Israel’s power, and yet Israel immediately attempted to break that sense of deterrence by offering to relinquish the newly conquered territories.

1975 Sinai Interim Agreement

The agreement established a buffer zone on the Sinai side of the Suez Canal, monitored by Egypt and the United Nations. This arrangement laid the groundwork for the later Camp David Accords.

Camp David Accords

In the late 70’s and early 80’s, Israel signed a peace treaty with Egypt which included returning the entirety of the Sinai desert to the Egyptians—including its strategic assets like oil fields—in turn for a mere piece of paper committing to peaceful relations.

Operation Litani

In 1978, following a terrorist attack, Israel launched an incursion into Lebanon, gaining control over significant portions of southern Lebanon. However, shortly thereafter, Israel withdrew, leaving a power vacuum that allowed terrorist groups to establish a stronghold in the region. This development ultimately set the stage for the First Lebanon War.

Madrid Conference

In the late 1980s, talk of “Autonomy” became popularized, with the hope that civil autonomy for the Arabs living in Judea, Samaria and Gaza would lead to peaceful relations. The Rebbe argued that this was a violation of Section 329, and would only lead to further bloodshed.

Oslo Accords

The Oslo Accords (1993) aimed to establish a framework for peace between Israel and the Palestinians, granting limited Palestinian self-rule in exchange for commitments to renounce violence. The Rebbe vehemently opposed such agreements, warning that territorial concessions would endanger Jewish lives and embolden terrorism rather than fostering true peace.

Counterarguments and Responses

Other Mentions

List additional letters, Sichos, etc., from the Rebbe on this subject, with links.

- All of Eretz Yisrael is on the border: Sicha, 10 Teves, 5738 - Audio

- The first time the Rebbe speaks about 329: Sicha, 10 Teves, 5738 - Audio

Further Reading

Here we will list other related books, articles, etc.

Make Peace, Chapter ??

Daas Torah, p.; p...

References

- ↑ Samuel 1, 23:1-2.

- ↑ Talmud Eruvin 45a.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Or Zaru’a, vol. 2, Laws of Shabbat, ch. 84.

- ↑ Rashi, Eruvin 45a.

- ↑ Sefer Zmanim, Laws of Shabbat 2:23.

- ↑ Shulchan Aruch Harav: Chapter 329 – For Whose Sake May the Shabbos Be Desecrated.

- ↑ The Rebbe first invoked this principle with relation to “Jewish flight” from Crown Heights in 1969. Address, 22 Nissan, 5729 (Toras Menachem vol. 56, p. 137; Sichos Kodesh vol. 2, p. 65); Here to Stay, JEM, Short Film.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Address, 9 Teves, 5738. Sichos Kodesh vol. 1, p. 366; Video; Audio. This seems to be the first time the Rebbe mentioned this law with regard to the Holy Land.

- ↑ Address, Purim, 5740. Sichos Kodesh vol. 2, pp. 353-354; Video, Audio.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Address, 19 Kislev, 5739. Sichos Kodesh vol. 1, p. 440; Audio.

- ↑ For example, 14 Tammuz, 5727 (Toras Menachem vol. 50 p. 241; Sichos Kodesh vol. 2 p. 299); 1 Elul, 5738 (Sichos Kodesh vol. 3 pp. 381-382; Audio).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Letter, Third Light of Chanukah, 5741, p. 1.

- ↑ Address, Simchas Torah, 5742. Toras Menachem vol. 1, pp. 279-280.

- ↑ The Rebbe repeatedly emphasized that prioritizing diplomacy over security was a critical mistake. For example, he criticized the focus on foreign relations and political considerations over the conquest of Jerusalem and the safety of soldiers during the Six-Day War (Address, 15 Tammuz, 5739. Sichos Kodesh vol. 3 pp. 361-362; Audio). Similarly, he opposed prioritizing diplomacy over more urgent and significant matters during the First Lebanon War (Address, 13 Tammuz, 5742. Toras Menachem vol. 4 p. 1849; Audio).

- ↑ In 1975, even before introducing 329 as a security paradigm, the Rebbe used the medical analogy for understanding security threats (Address, 19 Kislev, 5736. Sichos Kodesh vol. 1, pp. 248-249; Audio).

- ↑ Address, 1 Elul, 5738. Sichos Kodesh vol. 3, p. 380; Audio.

- ↑ Letter, 13 Shevat, 5714, p. 6.

- ↑ source needed

- ↑ For Ben Gurion's understanding, see Shabtai Teveth, Ben-Gurion and the Palestinian Arabs: From Peace to War (Oxford University Press, 1985) p. 294; Michael Bar-Zohar, Ben-Gurion: A Biography (New York: Delacorte Press, 1977) pp. 185–188.

- ↑ Address, Purim, 5740 - Sichos Kodesh vol. 2, p. 361; Audio.

- ↑ source needed